A First-Timer’s Guide to the French Quarter

Welcome to New Orleans — and the French Quarter. This neighborhood was the original city of New Orleans, a literally walled city founded by the French so they could command commerce coming up and down the Mississippi River.

Although this is the “French” Quarter — and is also known as the Vieux Carre (“Old Square”) — much of the historical architecture here is Spanish in origin. During its long history, New Orleans has been administered by the French, the Spanish, the French (again!), and the USA. Here are some can’t-miss destinations for those exploring the Quarter for the first time.

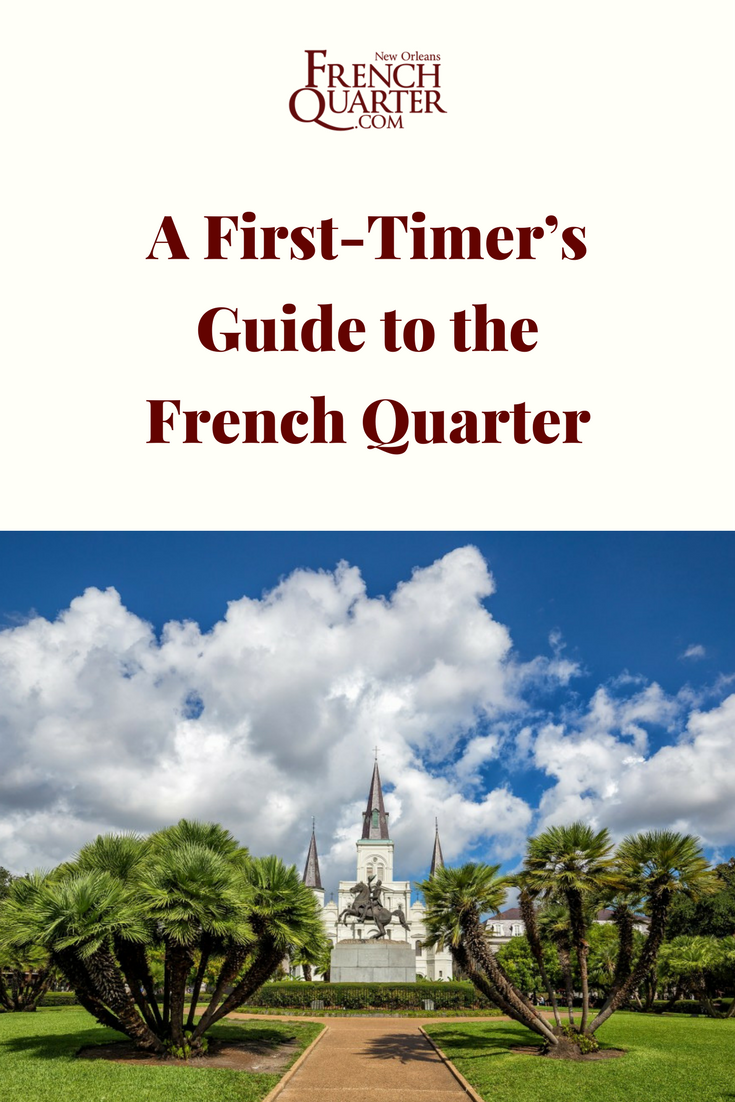

Jackson Square

If New Orleans has a town square, Jackson Square — dominated by St. Louis Cathedral and an eponymous statue of Andrew Jackson — is it. There’s a crackling energy here, which manifests amidst street artists, friendly fortune tellers, and busking brass bands.

The Square is hemmed in on either end by the Pontalba Buildings, one-block-long four-story brick buildings built in the late 1840s. Besides their handsome appearance, the top floors of the Pontalba Buildings house supposedly the oldest rented apartments in the USA (the ground floors are given over to shops).

St. Louis Cathedral, the oldest cathedral in the country, is the dominant landmark in the Square.

The Cabildo in Jackson Square courtesy of Louisiana State Museum on Facebook

The Cabildo

Jackson Square

New Orleans fairly drips with history, more so than almost any other American city (alright, we see you Boston, Philadelphia and St. Augustine). If you want an introduction to that history — indeed, to the story of Louisiana itself — make sure to drop into The Cabildo. Once a seat of local government and judiciary, today the building is managed by the Louisiana State Museum. Each floor gives insight into the past via exhibits on the different ethnic groups that have inhabited the state, the local history of colonization and Francophone identity, and the legacy of slavery and Civil Rights.

Pirate’s Alley

Off Jackson Square

This thin thoroughfare almost feels like an urban afterthought given the scale of some of the other streets in the French Quarter, but walking down Pirate’s Alley — which takes but a few minutes — is a quintessential French Quarter stroll.

This little street (it’s only 600 feet long), backed by historical buildings and packed with unique businesses like Faulkner House Books and the Pirate’s Alley Cafe and Absinthe House embodies a certain element of French Quarter identity: an unreplicable hybrid of architectural preservation and idiosyncratic eccentricity.

For what it’s worth, the legends that Andrew Jackson met pirate Jean Lafitte here for a clandestine pow-wow are probably that — myths. If a powerful official was going to meet with a wanted pirate, they probably wouldn’t do so on a pedestrian alley that ran alongside the city’s then-largest church.

Beignets from Cafe du Monde by Peter Burka

Cafe Du Monde

800 Decatur Street

We’ll be brutally honest here: Sometimes, when you hit Cafe du Monde during the busy part of the day (which can vary, although there’s almost always a crowd on weekends), it can be a bit too much. The whole point of sipping a cafe au lait and snacking on a beignet is to slow down, open your eyes and take in the street scene of New Orleans in a state of relaxed contemplation.

It’s tough to do this when you’re standing in line with 40 other people. But the times when du Monde is relatively slow (we like visiting late at night or early in the morning — don’t forget, it’s open 24 hours) are something like magic — it’s you, the city, some good coffee, and a pastry dusted in enough sugar to fund several dentists’ offices.

French Quarter Visitor Center

419 Decatur Street

This small branch office of the National Park System may seem a little underwhelming at first blush, but stop in and talk with a ranger and you’ll understand why this is one of the cultural cornerstones of the Quarter. The staff here are intimately tied to the city’s music scene and can direct you to any number of concerts and events where the best of New Orleans music will be showcased.

(Note: Due to ongoing projects to repair damages suffered from Hurricane Ida in 2021, the visitor center has temporarily moved to 916 N. Peters Street.)

Photo courtesy of French Market on Facebook

French Market

1008 N. Peters Street

Back in the day, when the French Quarter was more of a residential neighborhood, the French Market was truly that: a large, open-air bazaar where folks could find their daily produce and groceries. Today the market is divided into two portions: an upriver side collection artist stalls and food stands to showcase some excellent local crafts and cuisine, and a downriver side flea market, where you can find all kinds of souvenirs and trinkets ranging from cheap sunglasses to giant belt buckles to African wood carvings.

Adjacent to the upriver food stalls is Joan of Arc Park, a small plaza that includes a statue of the Lady of Orleans (i.e. “old” Orleans, i.e. the one in France).

Royal Street

Sure, you’ve heard about Bourbon Street — everyone has. Heck, we’ve even got the complete block-by-block guide to Bourbon Street. But it’s amazing how many visitors know plenty about Bourbon, yet rarely venture a block towards the river to see Royal Street — a thoroughfare that is equally fascinating, fun, yet sometimes seemingly a world away from the admittedly fratty behavior that can characterize Rue Bourbon. On Royal Street, you’ll find gorgeous architecture, elegant wrought iron balconies, and a glut of art galleries and antique stores — plus, some of the city’s finest restaurants.

Photo courtesy of The Chart Room on Facebook

The Chart Room

300 Chartres Street

There’s no shortage of great bars in the French Quarter, but few spots are as appealingly gritty and real as The Chart Room. It’s cheap, it’s cheerful, and it’s a world away from some of the other neon-bedecked theme bars you’ll find elsewhere in the neighborhood. They may not serve craft cocktails or fancy beer, but if we need a go-cup while we wander the Quarter, we head to The Chart Room.

The Moonwalk

Woldenberg Park

The Moonwalk is named for former mayor Moon Landrieu. It’s a pleasant little walk that offers excellent views out onto the largest river in North America, the mighty Mississippi. You’ll often find street performers, folks having a picnic, families on a walk, and a generally eclectic cast of New Orleans characters strolling around up here. Spot a riverboat, snap a picture, and soak up the scene.

Coop’s Place

1109 Decatur Street

Look, if you’re visiting New Orleans, you should eat your way through the whole city, but as you do, don’t miss Coop’s. Its blends the two distinct cuisines, Cajun and Creole, onto one excellent menu, the interior looks like a mad hallucination dreamed up by a bartender on a pirate ship, and the beer is cold. Sample some rabbit jambalaya or redfish or… well, you can’t really go wrong. Bon appetite!

Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop by Teemu008

Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop

941 Bourbon Street

Housed in a little stone building that looks like it dropped out of a timewarp (but for the modern mixers doling out frozen “Purple Dran”), Lafitte’s lays claim to being the oldest structure in the U.S. operating a bar. Come on in, listen to the local crooners bang out some piano tunes, and enjoy a drink in a true New Orleans landmark.

Are you planning to spend some time in New Orleans soon? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

The Historical Significance of Canal Street

Streetcars on Canal Street. Photo by Tom Bastin on Flickr

At a grand 171 feet wide, traversed by streetcars, taxis, automobiles, cyclists, and pedestrians, Canal Street is more than just a major downtown thoroughfare. Throughout its 216-year history, it also has served as an entertainment district, shopping destination, parade route, and above all, a gathering place for New Orleanians.

Stand on this broad, bustling street and you can see New Orleans’ history all around you — from the historic French Quarter to the Central Business District. You just have to know where to look. Here’s a guide to Canal Street, and what it means to the city of New Orleans.

The origins of Canal Street

Canal Street dates back to 1807, when French surveyor Joseph Antoine Vinache first conceptualized it. A canal linking the Mississippi River, Bayou St. John and Lake Pontchartrain was planned in the empty green common area that now comprises Canal Street, but it never came to pass. Instead, the wide median became the heart of downtown.

The “neutral ground”

Residential, commercial and government buildings flourished along Canal Street in the 1800s, which became the dividing line between the primarily Creole French Quarter side, and the primarily American sector, which is now known as the Central Business District. Tensions often arose between these two groups, but Canal Street was a “neutral ground,” a name that now extends to any median in New Orleans.

It’s electric

Canal Street is not only one of the widest streets in the country, but it was also one of the first streets in the world to be lit with electric lights, joining London, Paris and New York in this early technological achievement. By the mid-1880s, Canal Street was completely lit by electric lights.

Department stores Maison Blanche and D.H. Holmes dazzled pedestrians in the late 1800s with brilliant displays of electric bulbs that would pave the way for neon displays in the 1920s and 1930s. Some signs, such as The Joy Theater and the Saenger Theatre, look very much the same today as they did in the mid-20th century.

A shopping destination

Many older New Orleanians recount their childhood shopping experiences at Canal Street department stores with a nostalgic smile and a sigh. It was common to don one’s Sunday best, along with hats and gloves, to shop at Canal Street’s department stores.

Though these businesses had mostly shuttered by the end of the 20th century, recent years have seen a resurgence in downtown shopping. The upscale Canal Place, the recently renovated Outlet Collection at Riverwalk, and the two-story H&M in the French Quarter are all evidence that downtown is resuming its place as a shopping destination. Some retailers, such as the family-owned menswear store, Rubensteins’, open since 1924, or Meyer the Hatter, open since 1894, have never left the Canal Street area.

A gathering place

Canal Street is a place to congregate, celebrate and be entertained. Its movie palaces, now music and performance venues include the Saenger Theatre, The Joy Theater and Loew’s State Theatre (sadly, now shuttered and in disrepair). Each year, during the weeks leading up to Mardi Gras, hundreds of thousands of people congregate to watch Carnival krewes roll down the traditional Canal Street route, just as they have since 1857.

A glance at old photographs of past Mardi Gras reveals that while many aspects of Canal Street have changed, many others have remained the same. In Canal Street, perhaps more so than in any other part of the city, it’s easy to see both present and past shifting alongside each other, like a holographic snapshot of New Orleans’ many stories.

Are you planning to spend some time in New Orleans soon? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Type Spotting: Historic Building Styles in the French Quarter

A keen eye and quick list can unveil the salient patterns of French Quarter building types. Most antebellum sorts come in “Creole,” “American,” and a mix of the two. Those built after the Civil War and later are generally “Eastlake,” or sometimes “Craftsman” cottages.

There are subtle but fundamental differences among the types, and one must watch for variations not in “style” or décor, but in roof framing, massing, and floor plan. The entrance to a building is a clue to its original inside arrangement.

French & Spanish Influences

Public monuments on the Square include The Cabildo, begun in 1795 as a Spanish town hall in a modified Baroque style. The Presbytere, or priests’ home, is similar but, not completed until 1813, it was used as a courthouse. Both were built with Renaissance-style roof balustrades, with the Mansard roofs being added in 1847.

St. Louis Cathedral, built to designs of French architect de Pouilly, was begun in 1849 and is the fourth church on the site. The flanking Pontalba Buildings consist of two long rows of Creole townhouses, built by Baroness Pontalba in 1849 to embellish the square and increase her rents.

Glorious Creole Townhouses

The glory of the Quarter is its mass of Creole townhouses, with shops below and homes above. Of nearly equal significance is the distinctive Creole cottage, of squarish form, with side gables and steep, dormered half-story for children’s bedrooms.

The walls are frequently built of French-style bricks-between-posts and the roof slants front-to-back or may be hipped at one or both ends. This salient feature contrasts sharply with the roof of the later “shotgun cottage,” where the roof slopes side-to-side and is too low to accommodate an upper level. This allows decorative jigsaw embellishments to dominate the façade of the “shotgun.”

The Creole townhouse took shape after the fires of 1788 and 1794 removed the town’s freestanding French Colonial houses. These late Spanish years saw the rise of the tall, narrow, three-story brick house, set at the sidewalk, or banquette, with three bays or openings, all doors.

Inside the family entrance, but exterior to the shop, the house has a ground-level flagstone passageway leading to a loggia in the rear with a curving stairway. This is sometimes reached with a porte-cochere or carriageway. Stairs are never in a hallway.

Outside, doors are tall and surmounted by arched and barred transoms. Above them, one should note the narrow second-floor balcony, just two or three feet deep and supported by scrolling brackets of hand-wrought iron from the forge.

The cast-iron “gallery” of later vintage is different — wide and supported on columns, all cast from molds in commercial foundries, not from mom-and-pop blacksmith shops. These were frequently added in the 1850s to houses first built with balconies in the 1830s.

Look for the “Entresol Houses”

One may occasionally find a balcony oddly high up on the façade, as at Bourbon and Bienville (The Old Absinthe House) or Chartres and St. Louis (Maspero’s). These are examples of the enigmatic, interesting “entresol house” — the special cases of the Creole townhouse. With a short middle level or “entresol” between the shop and the residence that was used for stock and storage, these mezzanine spaces get light and air from extra high, arched and barred, first-story transoms. They were an experiment with full-service vertical living in the growing 18th-century city.

American Townhouses

The American townhouse looks like the Creole, but has an interior stair hall, post-and-lintel openings, and may have a five-bay center hall façade as at the Xiques House, 521 Dauphine. Dating from 1825 to the Civil War, they always have late Federal or Greek Revival ornament and are found in superb rows with cast iron galleries.

The American-style store has heavy granite columns and lacks an upper residence and thus a family entrance. The “corner store-house,” whether cottage or townhouse, has a beveled corner doorway, but keep an eye out for the subtle family entrance with molded door surrounds on a side wall.

Watching for these features will make Quarter sightseeing more readable for newcomers. The vigilant Vieux Carré Commission has jurisdiction over exterior walls, both front and rear, which preserves a fairly high level of historical accuracy in French Quarter streetscapes.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer, historian, translator, and archivist. She is known for her work in the New Orleans Notarial Archives as “Louisiana’s premier archivist” and her publications on New Orleans history.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

New Orleans Lingo: A Few Words to Know

Photo courtesy of Dirty Coast on Facebook

New Orleans is often described as the most European city in the United States — or the northernmost Caribbean island. Settled by Native Americans, colonized by the Spanish, French and American governments, populated by Creoles, African slaves and European immigrants, and surrounded by Acadian settlers (known as Cajuns), it’s no wonder the Crescent City’s residents have a way of speaking that doesn’t sound like anyone else’s.

The downside? This unique lexicon can make New Orleanians hard for outsiders to understand.

Here’s a list of key words to know before you go.

Alligator pear: Yat speak for an avocado (that skin DOES look like a gator’s tough hide).

Banquette: A sidewalk

Bo bo: A bruise, cut, scrape or other minor injury, usually sustained by a child. Never called a “boo-boo.”

Brake tag: An inspection sticker placed on a car’s windshield to indicate it is in good working order.

Cher: A Cajun term of affection derived from French and often pronounced “sha.” E.g., “You’re looking good, sha!”

Chicory: A bitter, roasted root brewed in lieu of coffee during France’s 1808 Continental Blockage and the U.S. Civil War, which New Orleanians continue to add to coffee because of its strong flavor. Best enjoyed in sweetened café au lait.

Coffee milk: A treat for young children, it consists of a dash of chicory coffee mixed with a cup of warm milk and sugar.

Dressed: A po-boy served “dressed” comes with lettuce, pickles, tomato, and mayonnaise.

Fixing to: Getting ready to do something. E.g., “I’m fixing to go to the store.” Also shorted to “fixina” or “finna.”

Gris gris: A Voodoo spell or charm, usually in the form of a small bag filled with rice, herbs, small stones, coins, or other amulets.

Go-cup: Like a to-go box you’d get at a restaurant to carry your leftovers, a go-cup is any plastic cup used to transport your unfinished alcoholic drink when you’re ready to leave the bar.

Gumbo: A spicy stew made with a roux base and thickened with okra, gumbo comes in seafood, chicken, sausage, and z’herbes (green) varieties, to name a few. Its name is derived from the African name for okra.

King cake: A delicious ring-shaped cake made of a cinnamon roll-like dough and topped with purple, green and gold sugar, with a tiny plastic baby inside. Whoever gets the baby has to buy the next king cake. Served only from Epiphany (January 6) until Mardi Gras.

Lagniappe: A little something extra, similar to a bakers’ dozen. E.g., when you dine at Brennan’s and get a free praline, that’s lagniappe.

Mais yeah: Cajun French saying that translates literally to “but yes,” it’s used to express excitement or agreement.

Make groceries: Yat speak for buying groceries, it’s derived from the French phrase “faire le marché” (make the market).

Merliton: A pale green squash-like gourd.

Neutral ground: Known as a median in other locales, a neutral ground is the wide grassy strip between streets.

Parish: The equivalent of a county. “The Parish” (or “Da Parish”) specifically refers to Chalmette, a New Orleans suburb.

Pirogue: A flat-bottomed Cajun boat, pronounced PEE-row or PEE-rogue.

River side, lake side: New Orleans speak for north and south: River side refers to the Mississippi River, which borders the city to the south, and lake side refers to Lake Pontchartrain, which borders it to the north.

Shotgun house: A long, narrow, hall-less house common to New Orleans, which was named so because if one fired a shotgun through the front door, the shot would go straight through the house without hitting a wall and exit through the back door.

Ward: Designations dividing New Orleans into 17 regions, or wards, which are subdivided into precincts.

Where y’at: Yat speak for “How are you?”

Wardies: People who live in your ward. Also pronounced “whoadies.”

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Style, Flavor and History: Exploring the “Grande Dames” of Creole Dining

By: Ian McNulty

Only in New Orleans — and perhaps only at Galatoire’s Restaurant (209 Bourbon St.) — would people greet with apprehension the news that soon they would no longer need to stand in line on the sidewalk to secure a table for dinner.

Eliminating that line was one upshot of the Creole restaurant’s renovations, completed in 1999, which created a second-floor barroom for patrons waiting to be seated in a dining room with a strict first-come, first-seated policy.

In the end, most of Galatoire’s regulars embraced this and other conveniences brought on by the renovation, but such is the reverence New Orleanians have for their city’s famous old-line restaurants that any change to tradition — even one involving standing and waiting in the outdoor heat — is regarded with suspicion.

Not merely old, historic restaurants, Galatoire’s and the other Creole “grande dames” of the New Orleans dining scene are deeply entwined in both the city’s social history and the traditions of many local families. The chefs and proprietors of these restaurants have made indelible contributions to the local culinary culture, and in the process engendered an almost uncanny loyalty among patrons and intrigue for new visitors.

Part of what makes these grande dames so compelling is how their cooking and service style so often serves as a boldface refutation of modern restaurant trends practiced fervently elsewhere. While many chefs and restaurateurs strive to discover the “next big thing,” these restaurants have grown famous for changing as little as possible over the course of generations.

The epitome of that proud status quo is on display at Antoine’s Restaurant (713 St. Louis St.). Founded in 1840 by the Alciatore family, Antoine’s is not only the oldest restaurant in New Orleans but also the oldest in America under continuous operation.

Formal and elegant, the restaurant is composed of a series of evocatively-named dining rooms (the “Mystery,” “Japanese” and “Proteus” rooms among them), all connected by an almost labyrinthine system of corridors. The restaurant’s ground-level wine “cellar,” visible through a small, barred window on the 500-block of Royal Street, seems to stretch on endlessly.

Antoine’s sprawling menu, written in French, could be a textbook for old-fashioned Creole cooking, featuring dishes like pompano en papillote — a superior local fish cooked in parchment with wine sauce — and grand desserts like baked Alaska. Among the more famous inventions of Antoine’s kitchen is oysters Rockefeller, which with its rich, green sauce was named after the American tycoon.

A Real “Stand Up” Bar

If Antoine’s extensive, French-language menu reflects its long history of serving Creole high society, Tujague’s (823 Decatur St.) origins as a lunch and dinner room for merchants and laborers of the French Market and riverfront show up just as clearly in its own menu.

In fact, there is no printed menu here, but rather a prix fixe selection of five courses recited by the waiter. There is a choice of four entrees, but otherwise, everyone in the restaurant eats the same thing — the same communal dining style common in 19th-century eateries.

Shrimp remoulade is a mainstay, as is a very flavorful boiled beef brisket. And after courses of garlic-laden chicken bonne femme and boozy bread pudding, coffee with chicory arrives served in short glasses.

Founded by French immigrants in 1856, Tujague’s is New Orleans’ second oldest restaurant (only Antoine’s is older) and its ambiance appears virtually unchanged from those antebellum roots. An elegantly simple saloon runs adjacent to the dining room, where generations of locals and visitors have sipped cocktails and quaffed beers. There are no stools at the bar, which perhaps helps concentrate patrons’ attention on the ancient French mirror stretching virtually the length of the long room.

The Lunch Rush

Mirrors also figure prominently in the ambiance of Galatoire’s. While the renovations mentioned above opened new seating areas on the second floor, locals know the real action is just inside the restaurant’s front door in a bustling, brightly-lit dining room lined with mirrors — all the better to scope out the who’s who scene of New Orleans dining.

Regulars jam the room for celebratory lunches that can last for many hours, as plates of crabmeat maison, green salad with garlic, trout meuniere, and shrimp Marguery are washed down by round after round of mid-day cocktails and wine.

Galatoire’s isn’t the only place where regulars convene almost religiously. Just around the corner at Arnaud’s (813 Bienville St.), some more well-to-do patrons actually sponsored tables to help finance a multi-million dollar renovation undertaken at the sprawling establishment in the early 1980s. In exchange for $10,000, a plaque was set above a particular table marking it as that customer’s own, while a $12,000 open tab was credited for him or her to return the investment with interest.

All it takes is a reservation to get a regular table for a meal here today, though the classic ambiance of the tin-ceiling, tile-floor main dining room and expansive lists of wine, cigars and liquors would make anyone feel like a high roller.

The restaurant was founded in 1910 by Arnaud Cazenave, a colorful French wine salesman who later came to be known as Count Arnaud, though the regal title was self-applied. Arnaud’s grew quickly, absorbing adjacent buildings and cottages to form a contiguous palace for dining that includes 12 private rooms on the second floor alone, as well as its own small Mardi Gras museum. The menu features the Creole classics with some updated recipes, and a jazz band performs in the front dining room in the evenings.

Creole cuisine, at its heart, involves the classic cooking traditions of the French, deeply modified by the natural abundance and different cultural influences encountered in their former colony, New Orleans. At Broussard’s (819 Conti St.), that Old World/New World dichotomy is reflected even in the surroundings.

Formal dining rooms set in a 19th-century mansion hark back to the opulence of imperial France, while the restaurant’s cobblestone courtyard with flowering trees and a babbling fountain offers a textbox vignette of the city’s lush subtropical splendor. Meanwhile, the menu mixes old with new as roasted rack of lamb and bouillabaisse share the stage with dishes like sugar-crusted ahi tuna.

Breakfast, Anyone?

The youngest of New Orleans stalwart restaurants is also perhaps its best known. Owen Edward Brennan, the son of a foundry laborer from New Orleans’ Irish Channel neighborhood, was already an accomplished bar owner when, in 1946, he opened a French restaurant on Bourbon Street bearing his family name. Brennan’s Restaurant (417 Royal St.) moved to its present location in 1956, occupying a grand old Vieux Carre building that dates back to 1795 and once housed the first bank to be chartered in New Orleans.

Almost from the start, the original proprietor set out to make breakfast the signature meal at Brennan’s, and indeed the restaurant has long been famous for its decadent morning repasts (which can and do last long into the afternoon). The meal traditionally starts with cocktails, moves through a selection of appetizers and classic egg dishes and wraps up with dessert, often Brennan’s own Bananas Foster.

And while breakfast “eye-opener” cocktails may be the traditional way to greet the morning at Brennan’s, during dinner the restaurant’s wine list takes center stage. With a truly staggering volume at 56 pages, the wine list runs to 3,000 offerings.

Are you planning to spend some time in New Orleans soon? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Exploring St. Louis Cemetery No. 1

Photo courtesy of Cemetery Tour New Orleans at Basin St. Station on Facebook

Former New Orleanian William Faulker famously wrote, “The past isn’t dead and buried. It’s not even past.” Nowhere is this truth more evident than in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. In this storied “city of the dead,” elaborate, crumbling above-ground graves hint at the stories of the larger-than-life personalities entombed within. As is true for many places in New Orleans, the veil between past and present feels very thin here.

It’s no wonder St. Louis Cemetery attracts more than 100,000 visitors each year. Some come to see the final resting place for Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau, while others come to tend the graves of loved ones interred within (St. Louis Cemetery remains an active gravesite). Still, others come to experience the city’s living history via a stroll through its oldest cemetery (St. Louis Cemetery was built in 1789). Regardless of your motivation, a trip to New Orleans wouldn’t be complete without visiting St. Louis Cemetery No. 1.

One caveat: Unlike most other New Orleans cemeteries, St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 is accessible only via the official, guided, licensed tour. That’s because the cemetery has been subject to much vandalism over the years. The tour tickets are $25 for adults and $18 for children. Tickets are available here: https://cemeterytourneworleans.com/.

Photo courtesy of Cemetery Tour New Orleans at Basin St. Station on Facebook

Here’s what to know (and a few things to look out for) before you go.

Dress for success

We’d be lying if we said New Orleans’ hot, humid subtropical climate never got the best of anyone. Any experienced tour guide will tell you they’ve had a tourist overheat. Why? It’s simple: The sun is intense, there’s very little shade in the cemetery, and the oven vaults block any semblance of a cool river breeze.

That’s why proper preparation is key, especially if you’re visiting during the warmer summer months. Bring a bottle of water, dress lightly, and don’t forget the sunblock. You may notice a few savvy tour guides sporting both wide-brim hats and parasols to block the sun. Properly prepare for the heat, and you’ll be able to get the most out of your visit.

It should go without saying that you mustn’t touch or desecrate the tombs, drink alcohol, or smoke in the cemetery. Photographs, on the other hand, are welcome — and your tour guide will be happy to snap a picture of your group.

With that in mind, here are a few things to know and prominent gravesites to watch out for.

Photo by Kathryn Valentino

The story behind the Cities of the Dead

Above-ground burials are just one of New Orleans’ idiosyncrasies, but they don’t exist solely for the sake of uniqueness. The city’s high water table makes in-ground burials impossible — a coffin buried underground simply floats back up to the top.

Once located at the marshy city limits, St. Louis Cemetery is now near the center of the city, thanks to the draining of the swamps, which permitted people to settle beyond the French Quarter.

One of the first things you’ll see when you enter St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 is a bank of “oven vaults” or “wall vaults” to your left. These tombs stack gravesites, filing cabinet style, one above the other. Glance at the ground, and you’ll see some graves are only partially visible — the rest are below the earth, evidence that New Orleans is gradually sinking.

Many oven vaults house the remains of countless family members. After a body is interred, it is left undisturbed in the grave for a period of one year and one day. At that point, the remains may be pushed to the back of the tomb, leaving room for another body to be interred. Other families prefer to collect the remains, placing them in a muslin bag.

If you wish to be buried in this famous graveyard, you can make it happen, but it’s going to cost you. It’s not unreasonable though when you consider the people who will become your neighbors for eternity. They include…

“The future tomb of Nicolas Cage” – St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 by Nelo Hotsuma

Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau

Born in 1801 in the French Quarter to a Haitian mother and white father, Marie Laveau gained prominence as a Voodoo practitioner. The beautiful young woman was also a hairdresser to the wealthy, learning many beauty tricks and herbal remedies from her mother.

She was known for her caring and benevolent heart, as she nursed many people who suffered during the yellow fever epidemics of the 19th century. She saved countless lives, and to this day, people think of her with gratitude.

Many believe she continues to work her magic from beyond the grave. That’s why you’ll see faint triple XXXs etched into her grave — a practice that is actively discouraged — or trinkets such as bobby pins left in threes. (Bobby pins and hair clips are an homage to Laveau’s past work as a hairdresser.)

Homer Plessy

In June 1892, Homer Plessy challenged segregation laws when he refused to disembark from a “whites only” train car at nearby Press Street. (A train still runs on those tracks today.) Plessy was convicted of breaking the law, and the case moved to the Supreme Court. In 1896, the “separate but equal” mandate was ruled constitutional, setting the stage for years of segregation and oppression. But the seeds of the civil rights movement also had been planted, thanks to Homer Plessy.

Nicolas Cage

Wait, he’s not dead yet, you might point out. You’re right. Nicolas Cage is 59 years old (in 2023) and seems to be in good health. However, he’s thinking about the future, which is one explanation for why he purchased a gleaming white, nine-foot pyramid inscribed with the Latin phrase “Omnia Ab Uno” (All from One).

The gravesite has baffled news outlets worldwide, whose reporters have come up with many different conspiracy theories. Among them: Cage is a closet Voodoo practitioner; Cage has Illuminati ties; Cage is an immortal who will entomb himself for a century before re-emerging; Cage has stored his wealth in the tomb.

Nobody really knows why he chose a tomb that’s so incongruous with its surroundings, but we do know it’s a very eye-catching construction, and that Cage evidently loves New Orleans.

Are you planning to spend some time in New Orleans soon? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Neighborhoods Near the French Quarter

Photo by Antrell Williams on Flickr

By some counts, there are as many as 73 neighborhoods in New Orleans. They are divided by the lakes, bayous, and the Mississippi River; by the railroad and streetcar tracks; and, sometimes, by arbitrary geographical boundaries.

The city is a culturally rich tapestry of its neighborhoods, with some of the oldest ones clustered around the French Quarter. They make up the core part of what makes the city unique and draws visitors to its architecture, history, food, and magic. Here’s a quick snapshot of the three of the neighborhoods adjacent to the French Quarter, and what to see, do, and eat there.

Photo of South Rampart by Cheryl Gerber

CBD/Warehouse District

Boundaries

The City Planning Commission defined the CBD as a 1.18 sq. mi. area bound by Iberville, Decatur and Canal Streets to the north; the Mississippi River to the east; the New Orleans Morial Convention Center, Julia and Magazine Streets, and the Pontchartrain Expressway to the south; and South Claiborne Avenue, Cleveland Street, and South and North Derbigny Streets to the west.

History

The Central Business District (CBD) was once the plantation of Jean Baptiste LeMoyne de Bienville, founder of New Orleans. The land changed hands until Bertrand Gravier subdivided the plantation after the fire of 1788, and named the subdivision Faubourg St. Marie after his deceased wife. After the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, the area experienced an influx of Americans, who built brick townhouses and Protestant churches.

What it’s like today

The modern CBD is a long departure from its 18th-century, largely residential ancestor. It’s now home to many office highrises, restaurants, boutique hotels, retail stores, and lots of historic commercial and residential buildings.

What to see and do

The area contains the South Market District, an upscale shopping destination, and Orpheum, Joy, and Saenger theaters. The area around Canal Street, which borders with the French Quarter, is home to numerous retail stores and restaurants, as well as the Audubon Aquarium of the Americas, the Insectarium, and Harrah’s casino.

Clusters of art galleries on Julia Street known as the Warehouse/Arts District, host openings on the first Saturday of the month and special annual events like White Linen Night. There’s much to see at the Contemporary Arts Center, the World War II Museum, and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art. The Superdome, the Ernest Morial Convention Center, and the Outlet Collection at the Riverwalk are all located in the CBD.

Get a taste of how Mardi Gras is done by touring Mardi Gras World, find a statue of the Confederacy of Dunces hero Ignatius J. Reilly at the site of the now-closed D.H. Holmes department store on the 800 block of Canal St., or walk the trendy Warehouse District, restored to its former industrial glory — to get the feel of what was the “American Sector” of the city.

CBD is remarkably easy to access from other areas of the city too: Cross Canal Street, and you’re in the French Quarter. Several streetcar lines can take you to Mid-City, Marigny, and Uptown. If you walk to the river, you can take a ferry to Algiers on the West Bank.

Where to eat, drink and hear music

The culinary destination hits keep coming, especially in the Warehouse District, so there’s no shortage of innovative restaurants to choose from. Donald Link’s Cajun-Southern Cochon on Tchoupitoulas Street has some of the best pork ribs in the city. Justin Devillier, the chef and co-owner of the New Orleans restaurants La Petite Grocery, is a James Beard Award winner and multiple-year finalist.

The curried goat by chef Nina Compton at Compere Lapin is divine, and draws from the Caribbean culinary influences of the chef’s native St. Lucia. Herbsaint is always a good choice for the upscale-French dining experience, and Domenica has some of the best pizza in the country.

The nightlife in the CBD is best represented by Republic NOLA, a music venue and nightclub in a former warehouse space.

Photo of the Candlelight Lounge by Cheryl Gerber

Treme

Boundaries

The 442-acre Treme is defined by Esplanade Avenue to the east, North Rampart Street to the south, St. Louis Street to the west, and North Broad Street to the north.

History

It’s one of the oldest neighborhoods in the city, settled in the late 18th century and heavily populated by Creoles and free people of color. The area was named after Claude Treme, a French hatmaker and real estate developer who migrated from Burgundy in 1783.

What it’s like today

Treme is known for its music clubs and soul food spots (many double as both), Creole architecture, and cultural centers celebrating the neighborhood’s African-American and Creole heritage. It’s a vibrant, diverse neighborhood, home of many a second line parade and the onetime star of popular HBO’s namesake series.

What to see and do

The beautiful St. Augustine Church is the most famous African American Catholic church in the city (though not the oldest). It was founded by free people of color in 1842. Don’t miss the Tomb of the Unknown Slave, a tribute to the victims of the African diaspora, located on the church grounds at 1210 Governor Nicholls Street. Two blocks away, on the same street, is the New Orleans African American Museum of Art, Culture and History.

Treme is also home to the excellent Recreation Community Center. You’ll find an incredible collection of Mardi Gras Indian costumes and other cultural memorabilia at the Backstreet Cultural Museum, founded (and manned for many years) by the late Sylvester Francis.

One of the city’s most famous “cities of the dead,” St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, is located at Basin and St. Louis Streets. (You may remember it from Easy Rider.) Civil rights activist Homer Plessy and voodoo queen Marie Laveau are buried in this cemetery, which was founded in 1789. Across N. Rampart Street from the French Quarter stretches the 32-acre Louis Armstrong Park, home to the Mahalia Jackson Theater of the Performing Arts, the iconic Congo Square, Armstrong’s statue, and several annual food and music festivals.

Where to eat, drink and hear music

Treme is said to be the birthplace of jazz, and it’s still a great place to hear live music. The Candlelight Lounge is an excellent option for Creole food and brass bands. Kermit’s Treme Mother in Law Lounge on N. Claiborne belonged to the late R&B and jazz legend Ernie K-Doe and his wife Antoinette. When both passed, Kermit Ruffins bought it and continues the tradition with live music and BBQ.

A legendary soul food restaurant is Dooky Chase’s. The late chef Leah Chase’s Creole staples include gumbo z’herbes, which is not easy to find on the restaurant menus in the city. It’s a meatless version of gumbo made with several types of greens.

Not far away on Orleans Avenue, Greg and Mary Sonnier reopened in the fall of 2017 their famous restaurant, Gabrielle, which used to be in Mid-City on Esplanade Avenue, but has been shuttered since Katrina. And, speaking of Esplanade, Li’l Dizzy’s Cafe is a popular choice for a casual soul-food breakfast.

Walking in the Marigny by Cheryl Gerber

Marigny

Boundaries

North Rampart Street and St. Claude Avenue to the north, Press Street to the east, the Mississippi River to the south, and Esplanade Avenue to the west.

History

Marigny is named after Bernard de Marigny, a French aristocrat with well-documented joie de vivre, whose plantation and its subdivisions formed the area in the early 19th century. Just like Treme, the neighborhood was inhabited by a vibrant mix of Creoles and free people of color.

What it’s like today

Faubourg Marigny is one of the city’s most densely populated neighborhoods with an eclectic mix of residents. It’s peppered with excellent bars and restaurants, covetable historic houses, and iconic music venues. It should also be lauded for the lack of retail chains, its walkability, and the fact that it’s one of the oldest gayborhoods in the South.

What to see and do

Just taking a walk down Royal or Chartres streets will be immensely rewarding because of all the Creole cottages, funky little stores, and bars and restaurants. Or take a stroll down Frenchmen Street any time of day. Most music shows start later at night, but you don’t even have to enter any clubs to hear an excellent brass band — it’s often spilling out on the street corners. It’s also home to a sprawling indie record store, Louisiana Music Factory.

On Elysian Fields by Frenchmen is Washington Square, a lovely little park with swaths of green and a small playground. The Healing Center on St. Claude Avenue is a multi-story community center that contains restaurants, a bookstore, a botanica, a performance space, a co-op, and more.

Where to eat, drink and hear music

Frenchmen Street and St. Claude Avenue have the highest concentration of live music venues, including the legendary The Spotted Cat and d.b.a. Though increasingly packed, Frenchmen Street is still an unsurpassed destination for local music and nightlife. Many nightclubs double as excellent restaurants, like the upscale Marigny Brasserie (sidewalk dining!), the popular Snug Harbor Jazz Bistro with its big acts and Creole fare, or the Three Muses (small plates, great music shows).

The cozy and romantic Adolfo’s is not easy to spot (it’s upstairs from the live-music hangout dive Apple Barrel), and has some of the best seafood on its Creole/Italian menu.

Marigny Opera House on St. Ferdinand Street, a popular performance venue with great acoustics converted from the church that was built in 1853, hosts everything from puppet shows to Sunday musical meditations.

Marigny is home to a slew of neighborhood bars you wouldn’t want to leave, like the Friendly Bar, Buffa’s (with live music and bar food), the R Bar, and many more. The bi-level Anna’s (the former spot of Mimi’s in the Marigny) has rotating food popups like tacos, pool, themed nights, and live music upstairs.

SukhoThai is a popular neighborhood restaurant with exposed brick and specialty Thai cocktails, or head to the Bao & Noodle on Chartres Street on the edge of the Marigny for Chinese tapas. The AllWays Lounge & Theatre, Siberia, and the Hi-Ho Lounge on St. Claude are all great choices on any given night for indie bands, DJ nights, burlesque, and experimental music and theater shows.

Are you planning to spend some time in New Orleans soon? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

French Quarter Like a Local

Photo by Cheryl Gerber

The French Quarter is without a doubt the most touristy neighborhood in New Orleans — but is it also a place where locals hang out? Are there even French Quarter locals?

Yes and yes. To be fair, the Quarter isn’t the residential neighborhood it once was. Well into the mid-20th century, this was a place where families hung out to do laundry and children walked to school. The famous French Market really used to be the local grocery store, in the sense that it was a spot where you could pick up produce and similar goods.

This dynamic has obviously changed over the years. The Quarter has evolved into a place primarily aimed at visitors, and the residents that remain do not tend to raise children in the neighborhood, with a few exceptions.

This evolution reflects the Quarter’s changing identity — it has shifted, over the decades, more into a place to play as opposed to a place to live. But let’s not forget: New Orleanians like to play. And many locals prefer to play in the Quarter, which has a mind-boggling number of restaurants, bars and shopping opportunities.

Photo courtesy of Mary’s Ace Hardware

Where to Shop

Chi-wa-wa ga-ga

511 Dumaine Street

Chi-wa-wa ga-ga is amazing because it’s not just a pet store — a brand of business where the mom-and-pop outfits are getting rarer and rarer — it’s a pet store specifically aimed at small pets. Yes, visitors often pop their heads in, but the main clientele are those New Orleanians toting around small dogs (and sometimes cats) who are in need of a costume for their little loved ones. Because sometimes, darn it, we just need to emphasize the identity of our wiener dogs by putting them in adorable little hot dog suits.

Speaking of pets, if you’ve traveled to New Orleans with a furry (or scaled or winged) friend in tow and they need some medical attention, try The French Quarter Vet (3041 N. Rampart Street) or the Pet Care Center (938 Esplanade Avenue). Both offices are friendly, helpful, and accustomed to dealing with patients from out of town.

Fifi Mahony’s

934 Royal Street

New Orleanians are serious about their costuming (also known as masking), and those who are in need of a specialized wig or hair piece to set off their outfits head to Fifi’s. It may not be the cheapest wig shop in the city (although the prices are actually quite reasonable), but as far as quality and attention to detail go, you just can’t do better. Plus, there’s always a scene here: drag queens and hair stylists, models and artists, all hanging out and trading the best costuming tips. If you’re into glitter, sparkles, and generally looking fabulous, Fifi’s has got you covered.

Mary’s Ace Hardware

732 N. Rampart Street

Hold up: you’re on vacation. In New Orleans. Why do you need to go to a hardware store? This author had to deal with a Mardi Gras costume emergency a while back with some visiting friends. Who came to the rescue with some Gorilla Glue and random timely advice on how to fix a stain on a hardwood floor? The folks at Mary’s Ace Hardware, a spot where you’ll find almost no tourists, but a bunch of New Orleanians who are doing what they need to do to fix up their homes (or costumes, as the case may be).

Porter Lyons

631 Toulouse Street

What’s neat about Porter Lyosn isn’t the fact that this is jewelry with a Louisiana twist. There’s plenty of that to go around in this state. What’s unique is the way owner and Tulane graduate Ashley Porter utilizes local materials — from agates to nutria fur to alligator skin to labradorite — to form pieces that are truly grounded in the Pelican State’s identity. There’s no shortage of jewelry stores in New Orleans, but you’ll often find locals shopping here simply because they know they can find something heartfelt and unique

The Quarter Stitch

629 Chartres Street

We mentioned earlier that New Orleans is the kind of place where people like to get into costume. That’s another way of saying New Orleans is crafty, and when the crafty folk need to get their DIY on, they often come here. There’s a plethora of needlepoint and yarn supplies at this Chartres Street store, as well as bins of beads, bling, and anything else you need to create a perfect costuming (or otherwise fashionable) statement.

Trashy Diva

537 Royal Street

The Diva is a longtime favorite for New Orleanians who want to glam out in mid-century retro style fashion. You can find gorgeous dresses and funky accessories that come in a wide, inclusive array of sizes for any and all body types.

Photo courtesy of Galatoire’s Restaurant on Facebook

Where to Eat

Acme Oyster House

724 Iberville Street

Acme is one of the more established oyster houses in the New Orleans pantheon, and it remains a favored destination for those locals in need of something delicious on the half shell. There’s something to be said for consistency, and this is what Acme provides: skilled shuckers who work fast to get you a glistening plate of Gulf-sourced goodness. While we tend to prefer our raw oysters straight, you shouldn’t leave town without trying an oyster shooter.

Brennan’s

417 Royal Street

A long, leisurely breakfast, accompanied by plenty of “eye openers” (before-noon cocktails) is a New Orleans tradition, and Brennan’s has been packing locals in for this ritual for years. While it’s been recently renovated, Brennan’s retains an old school, Creole charm, which makes for an attractive atmosphere as you scarf down eggs sardou and turtle soup. This spot is further commendable for its efforts to locally source from area farms and other food providers.

Dickie Brennan’s Bourbon House

144 Bourbon Street

It may be located in the very heart of the Quarter, but the Bourbon House is a longtime favorite for workers in the neighborhood and CBD who want some good seafood to accompany a drawn-out lunch (or a decadent dinner). We’re a city that loves its seafood, so you better believe the locals’ stamp of approval goes a long way here.

Felipe’s Taqueria

301 N. Peters Street

While New Orleans is world-famous for its food, not many people come here for Mexican cuisine. But when locals are in need of a quick burrito or taco, many head to Felipe’s. It’s cheap (you can fill up for under $10 a person, especially if you skip a drink), it’s filling, and honestly? It’s really good — this may be a local spot, but we also have friends from South Texas who attest to the reliability and tastiness of Felipe’s.

Galatoire’s

209 Bourbon Street

Galatoire’s doesn’t just attract locals — it attracts a specific cast of the city’s old money and high society, who are particularly known to pack into this iconic restaurant for Friday “lunches” that tend to last until the last bottle of champagne is emptied and everyone is heading to sleep. How local is Galatoire’s? The last time we went, our host brought “his” server a present — a portrait of the server.

GW Fins

808 Bienville Street

It takes a lot to divert old-school New Orleanians from their favored dining institutions, but GW Fins has managed to do so in a neighborhood packed with grand dame Creole restaurants. This spot specializes in seafood, and its version is simply some of the best in the city. The menu changes with availability but be assured that what comes to your plate is consistently fresh and delicious. An enormously popular date-night option for those New Orleanians who are in the mood to splurge.

Verti Marte

1201 Royal Street

There is no shortage of po-boy shops in New Orleans, but there’s a surprising lack of really good examples of the genre within the Quarter. Then Verti Marte raises its hand, as if to say: Hey, we’re open all the time, and we got good grub. And do they ever, particularly the sandwiches, which are several meals packed between two loaves of bread.

Cosimo’s by Cheryl Gerber

Where to Drink

Cosimo’s Bar

1201 Burgundy Street

A true neighborhood bar located within the more residential side of the Quarter, near the Marigny and Treme, Cosimo’s is simply a very nice bar. There’s a great jukebox and potent drinks, plus a cast of locals to keep things interesting as the night goes on.

Erin Rose

811 Conti Street

If you’re a member of the service industry in New Orleans and you’re out for a night in the Quarter — or if you’ve just kicked off of work — chances are you’ll end up in the Erin Rose. This is a small, cozy little dive tended by sassy staff, doling out strong drinks for the people who serve you strong drinks (and food).

Port of Call

838 Esplanade Avenue

To be fair, Port of Call is as much a restaurant as a bar, and locals do love to come here for the excellent burgers. But we’d be remiss to not mention some of the amazingly powerful mixed drinks available here, ranging from the Red Turtle to the Windjammer. All of the above concoctions go heavy on the fruit — and the spirits, so be careful.

If you’re planning a stay in New Orleans, be sure to check out our resource for French Quarter Hotels.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

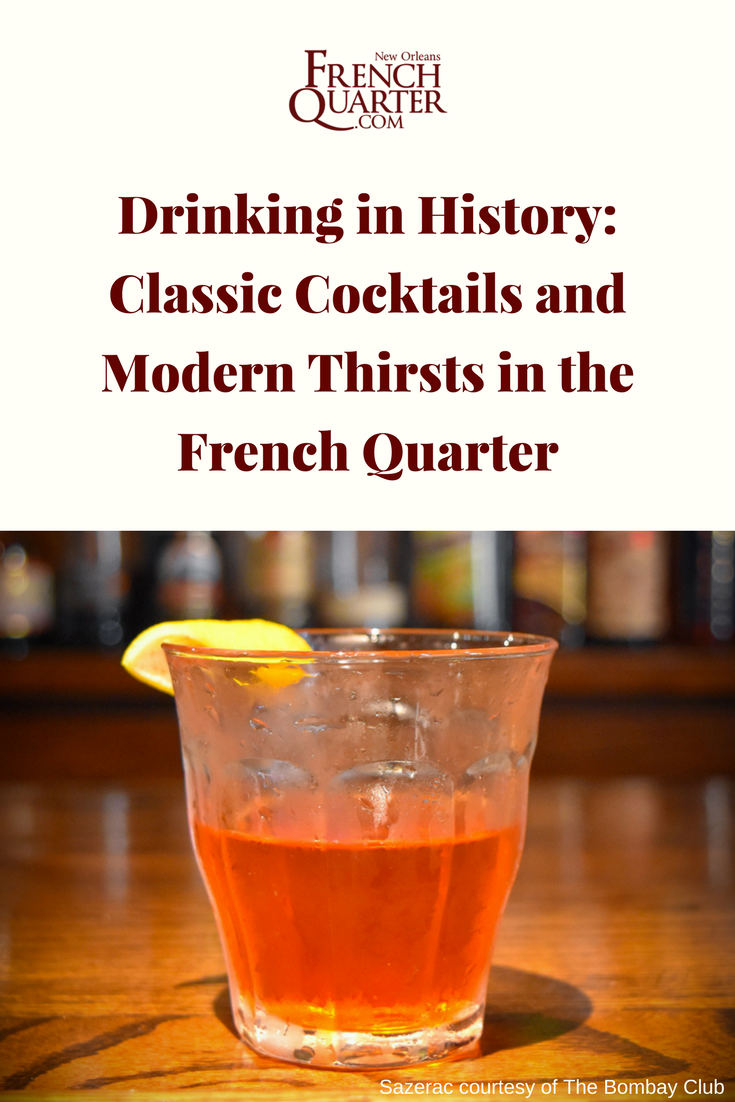

Classic Cocktails and Modern Thirsts in the French Quarter

Sazerac courtesy of The Bombay Club

If a traditional French Quarter breakfast can end with a dessert, maybe it’s not so surprising that it can also begin with a cocktail.

Indeed, at Brennan’s Restaurant (417 Royal St.), the lavish and almost canonized breakfast menu includes an entire page of cocktail recommendations that the landmark establishment introduces as “eye openers.” Many of these drink selections are as unique to New Orleans as the intricate egg dishes and flaming desserts that follow, with names like sazerac, Ramos gin fizz and milk punch.

Welcome to the rich and distinctive cocktail culture of New Orleans. The city that has a worldwide reputation for good times and hearty indulgence also has its own lore and history for the stuff that helps fuel its many celebrations — even if that celebration is nothing more than a courtyard breakfast.

Bourbon Milk Punch by Patrick Truby

Milk Punched in the Morning

Milk punch is an instructive starting point. Made with milk, sugar, brandy, and a little nutmeg, the drink is a creamy and sweet answer to the more common bloody Mary. It’s the sort of cocktail to enjoy while the sun is shining, and preferably when there are no responsibilities scheduled for the rest of the day. Many of the finer restaurants around the Quarter serve it well, and a surprising number of the smaller restaurants and cafes have a distinctive take on this morning favorite.

Hurricane by Kevin Galens

Hurricane Warnings Nightly

New Orleanians live with a profound respect for the naturally-occurring hurricane — small wonder in a town largely below sea level — but visitors might sooner associate the city with the fruity Hurricane cocktail. Certainly one of the most visible beverages in the French Quarter, this bright red, rum-based drink is the de facto emblem for the bar that created it, Pat O’Brien’s (718 St. Peter St.), and has been widely copied around town. Highly potent, the drink has been known to supercharge a night on the town and brighten up even the most overcast day in the Quarter.

The story of the drink’s origin holds that, due to difficulties importing Scotch during World War II, liquor salesmen forced bar owners to buy up to 50 cases of their much more abundant rum in order to secure a single case of good whiskey. The barmen at Pat O’Brien’s soon came up with an alluring recipe to clear through their bulging surplus of rum. When they decided to serve it up in a tall, jaunty glass shaped like a hurricane lamp, the hurricane cocktail was born.

Today, even the glass itself is a souvenir of New Orleans, and servers at Pat O’Brien’s will helpfully box yours to go when you’re finished.

Sazerac by Krista

Sazerac, the Quintessential Cocktail

The origins of the sazerac are quite a bit murkier, with some sources proclaiming it as the very first cocktail and more than a few local bon vivants naming it as New Orleans’ quintessential cocktail. A combination of rye whiskey, bitters, sugar, lemon peel, and an absinthe substitute (such as Pernod or Herbsaint), the cocktail is rich and complex, an elegant sipping drink to be sure, and is typically served in the finer Creole restaurants and classic barrooms.

A cocktail this intricate deserves careful preparation and proper presentation, which happily are two of the hallmarks of The Bombay Club (831 Conti St.), located in the Prince Conti Hotel. Fittingly, The Sazerac Bar (130 Roosevelt Way) in The Roosevelt Hotel, just on the other side of Canal Street from the Quarter, also serves a commanding version of its namesake drink.

Ramos Gin Fizz by Edsel Little

Drinking a Flower

The same bar lays claim to being the birthplace of the Ramos gin fizz, named for the hotel bartender Henry Ramos who is said to have invented it in 1888. This unique concoction mixes gin, lemon and lime juices, orange flower water, egg white, powdered sugar, and milk, and has a taste that has been described as “drinking a flower.” In the French Quarter proper, the Carousel Piano Bar and Lounge (214 Royal St.) in the Hotel Monteleone is an appropriately elegant setting to sample one, with its slowly revolving bar and plush appointments.

Tropical Isle by Quinn Dombrowski

Tropical Isle by Quinn Dombrowski

Bombs Away

Far, far on the other end of the spectrum is the Hand Grenade, truly a Bourbon Street original that proves not all of the city’s distinctive drinks are rooted in the past. The drink is prepared and served at several French Quarter outposts of the Tropical Isle (435 Bourbon St., 610 Bourbon St., 721 Bourbon St., and 727 Bourbon St.), but, since it is often taken to go, its memorable neon-colored, hand grenade-shaped containers can be seen swinging from the happy hands of visitors all over the Vieux Carre.

The drink even has its own mascot, a character dressed in an inflatable grenade costume, who bounces around Bourbon Street encouraging consumption. If he ever encounters a true hurricane on his travels, it will surely be a historic encounter for New Orleans mixology.

Photo courtesy of The Old Absinthe House on Facebook

Absinthe Frappe

Absinthe was once a drink that was considered so dangerous it was outright banned in many countries (including this one, up until 2007). How does New Orleans deal with this potentially dangerous spirit? We make it more accessible by converting it into frappe form. This mint green drink is both refreshing and a little worrying; it’s one of those cocktails that doesn’t let you know how strong it is (strength? Kicked by a donkey) until it’s a little too late.

So where should you settle in for an Absinthe Frappe served right? Most locals will tell you to head to The Old Absinthe House at 240 Bourbon St. (imagine that), a buzzing Bourbon Street bar where locals and tourists rub shoulders and chase the green fairy.

Brandy Crusta by Krista on Flickr

Brandy Crusta

Have you ever had a Brandy Crusta? Neither have we. This early incarnation of the modern sour drink featured heavy use of cognac and Grand Marnier, as well as some other goodies like simple syrup and lemon juice. If all of the above sounds familiar, you’re likely thinking of the Sidecar, a contemporary drink that was invented right here in New Orleans in the 1850s (sadly, the hotel at the heart of that invention is no longer with us).

Brandy Crustas may be tough to find, but any competent New Orleans bartender should be able to serve you up a Sidecar at a moment’s notice. While we don’t have a clear favorite spot for those drinks, the ones fixed up the Kingfish (3337 Chartres St.) have always been top-notch.

Photo courtesy of Antoine’s Restaurant on Facebook

Cafe Brûlot

The café brûlot is no ordinary after-dinner coffee. The name, in French, means either “highly seasoned” or “incendiary/fiery” coffee, and both of those descriptions really get at what you’re about to drink. Drinking café brûlot is a production that requires specialized ingredients and even tools. Waiters bring, per our story on the spectacle, “orange peel — cut precisely as one long spiral; a lemon peel cut into strips; sugar, cloves and cinnamon; cognac or brandy and hot, strong black coffee”.

All of these ingredients are slowly ladled together and — why not — set on fire during an elaborate tableside ritual that forms one of the greatest set pieces of New Orleans gastronomic theater.

Obviously, a café brûlot isn’t some drink you can just rock and order at any old bar — it’s an after-dinner affair best enjoyed in old-line restaurants like Antoine’s (where the drink was supposedly invented; 713 St. Louis St.), Arnaud’s (813 Bienville St.), or Galatoire’s (209 Bourbon St.).

Photo courtesy of Old Absinthe House on Facebook

Frozen Irish Coffee

Was frozen Irish coffee invented in New Orleans? We doubt it, but this city lays claim to some of the best versions of this delicious drink, which is a sweet and sassy way of giving yourself both a caffeine and liquor boost. The drink comes out like a milkshake, and can taste dangerously un-boozy; be careful, a few of these can get to your head. Both Erin Rose (811 Conti St.) and Molly’s at the Market (1107 Decatur St.) are known for their frozen Irish coffees, which are unsurprisingly a hit with service industry workers who need a pick me up even as they take the edge off.

Coming to New Orleans soon? Be sure to check out our resource for French Quarter Hotels.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

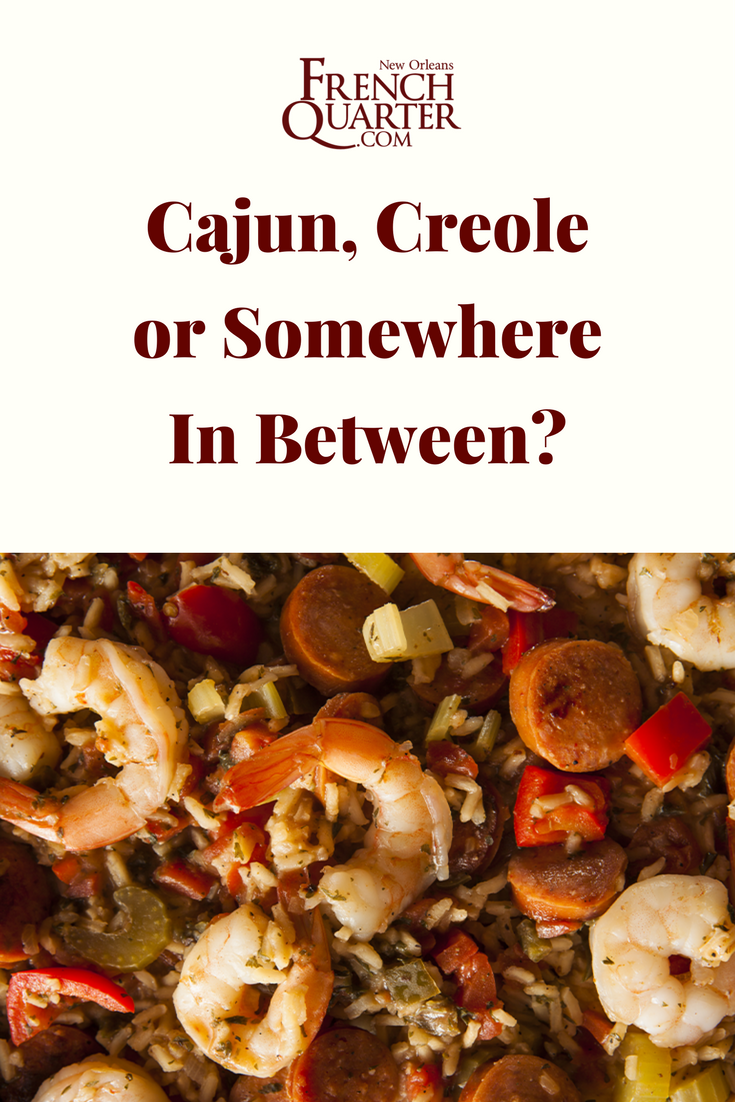

Cajun, Creole, or Somewhere In Between?

Visitors can be forgiven for some confusion over the difference between Cajun and Creole cuisines. After all, many life-long New Orleanians have trouble articulating just what separates one from the other, while national chain restaurants have long obscured the distinction with vague menu descriptions of “spicy Cajun-Creole” dishes, which may or may not have any connection to Louisiana.

Adding to the confusion are the many similarities between the two cuisines, which both evolved under heavy French influence, often use the same ingredients and sometimes even feature dishes with the same names, though these can appear and taste noticeably different.

Country-style vs. City-style

For the newcomer trying to sort it all out, a key point to remember is that Creole cooking came out of the kitchens of New Orleans restaurants, supplied by the commerce of a rich port and served to city dwellers. Conversely, Cajun cooking came out of the country, using whatever could be trapped, hunted or harvested from swamps and bayous and generally served family style. Indeed, famed Louisiana chef John Folse once explained the difference with the anecdotal quip that Cajuns eat in the kitchen and Creoles eat in the dining room.

One way diners can tell which type of cuisine they’re getting is to take a look at the groceries that went into a particular dish. Cajuns have an abiding love for pork and also use crawfish in large quantities when in season. Creole chefs are much more likely to use oysters, shrimp and crab meat than their Cajun counterparts.

Cajun cooking also tends to be spicy, thanks to healthy doses of cayenne or bottled hot pepper sauces, while Creole dishes are rich and flavorful but generally not spicy hot. Down-home meals of crawfish etouffee, smothered chicken and blackened anything are distinctly Cajun while famous New Orleans dishes like barbecue shrimp, trout meuniere or amandine and shrimp remoulade all come from the Creole side of the family.

Paella to Jambalaya

But it’s not always so easy to distinguish between the two traditions, as is the case with one of the most famous south Louisiana dishes, jambalaya. Considering the Spanish colonial history in New Orleans, it seems a very short leap to jambalaya from the Spaniard’s paella, the rice dish made with vegetables, sausages and seafood.

But there are other influences. The African restaurant Bennachin (1212 Royal St.) is named for a dish that looks and tastes much like an extra-spicy jambalaya. In fact, many of the dishes on the traditional African menu at this small, casual restaurant will look and taste familiar to anyone raised in southern Louisiana, even if the names and some key ingredients are completely foreign.

Bouillabaisse to Gumbo

Gumbo is a similar story. It looks like a relative of the seafood stew called bouillabaisse, which is native to coastal France and a dish the Creole New Orleanians certainly would have known. But a key ingredient in many gumbo recipes is okra, brought to the Americas by Africans, or filé powder of ground sassafras, adopted locally from Indians.

Africans even called okra “kin gumbo,” which is where this famous dish draws its name. Adding to this culturally diverse and tangled bloodline, there are separate Cajun and Creole renditions of both gumbo and jambalaya, with the Creole versions of each more likely to include tomatoes.

The distinctions are becoming increasingly academic when it comes to restaurant dining, however, and there is mounting evidence that Cajun and Creole traditions are evolving together towards one unified southern Louisiana cuisine.

For instance, no one will confuse Brennan’s Restaurant (417 Royal St.) with a Cajun eatery, but even at this Creole grande dame, the menu features dishes that take cues from both traditions, such as the eggs bayou Lafourche, a brunch classic with poached eggs over Cajun andouille sausage topped with Hollandaise sauce.

Similarly, diners can today find oysters Rockefeller, an invention of the Creole landmark Antoine’s Restaurant (713 St. Louis St.), all the way over in Lafayette, the unofficial capital city of Cajun country. Crawfish, which are harvested almost exclusively from Cajun country, are now increasingly common ingredients on Creole menus, where they had been virtually unheard of not long ago.

At their best, both Cajun and Creole cuisines draw from the abundance of Louisiana’s resources and are nurtured by cultures that celebrate the role of good food in family and social life. Compelling and deeply satisfying even on their own, when the two traditions get together they can throw an unbeatable culinary party.