Oldest Building Features of the French Quarter

Secluded in the muddle of the French Quarter’s raucous street life linger elements that still impart a kind of stately antiquity. They are Spanish and French-era pieces. Some are rightly celebrated for their survival of the epochs; others, dressed in garish costumes at the shop level, maintain a quiet dignity overhead.

There are only about a dozen known Colonial-era buildings in the Quarter. Surely more would have survived except for two late 18th-century fires. But armed with some simple guidelines, you can recognize the early types.

Check the corner of Chartres and St. Louis streets. There, on the river side of Chartres is a house with a well-known restaurant and a balcony. Note that the balcony is higher than usual, almost too high for the building. The arched, barred transoms under it are bringing light to a short middle floor called an entresol. This is where the old Spanish shopkeeper Juan Paillet kept his wares.

The entresol house was an early experiment in vertical living, with the shop on the ground floor, the warehouse in the middle, and an elegant residence on the upper level. Note the type at 440 Chartres, at Bourbon corner Bienville, at Royal corner St. Louis, and in mid-block at 500 Decatur. Most date to the 1790s.

Brennan’s Restaurant at 417 Royal Street is an example of a more elaborate business and residence of the late Colonial period. Dating to the 1790s, it was once a private bank and home. The Banque de la Louisiane, whose initials are on the balcony, made the building public in 1805. In the early 1900s, it first became a restaurant called the “Patio Royal.” It has been the home of Brennan’s since 1946.

The Girod House at 500 Chartres corner St. Louis, is better known as Napoleon House. Tradition abounds, both as to its one-time purpose as a haven for the deposed Emperor, and in modern times about the charms of its resolutely unregenerate bar. Its rear wing was built just after the Great Fire of 1794. The three-story main part, with its towering belvedere, dates to 1814. Above the tavern is an elegant salon and residence, now restored for entertaining.

Another private home in the grand style was that of Bartolome Bosque at 617 Chartres Street, dating to 1795. Its Arabesque monogram on the balcony represents the style of Spanish Colonial ironworking in New Orleans. This type of home is called a “Creole townhouse.” One accesses the rear by a porte-cochere or carriageway, and ascends the stairs in the rear of the building.

Creole townhouses never had inside stair halls. Bosque’s daughter Suzette was the third wife of the state’s first American governor, W.C.C. Claiborne. On his third try the governor finally married a Catholic, making better friends with the Creoles. She proceeded to outlive him.

Like the Bosque House, the Pedesclaux-Lemonnier House, 640 Royal at St. Peter, has a colonial origin. Begun by the grand old Spanish notary Pedro Pedesclaux, it was sold to a doctor from the islands. In 1811, Dr. Yves Lemonnier had the building enlarged, adding his initials to the balcony. His curved-wall salon on the second floor is the finest in the Quarter. After the Civil War, a later owner added the fourth floor, making it a “skyscraper.” The building was identified with George Washington Cable’s romance “Sieur George” in later decades. Today it is sadly hung with t-shirts.

The old Spanish Cabildo and The Presbytere, or priests’ house, flanking the St. Louis Cathedral, were designed for the Spanish governing council by Guillemard, a French-born architect. The Cabildo, built in the style of Spanish town councils in Spain and the Americas, was begun in 1795.

The Presbytere has never housed clergy, although buildings underlying its site were always the priests’ residence. Also begun in 1795, it was not completed until 1847 and was used for most of its history as a courthouse. The Mansard roofs on both buildings were added in 1847. For nearly a century both buildings have been part of the Louisiana State Museum.

“Madame John’s Legacy,” another Museum property at 632 Dumaine, is also named for a romance by Cable. Dating to 1788, it was built immediately after the great fire that year, duplicating the house type of the French Colonial era. With its free-standing mass and surrounding galleries, it is more like a French West Indies home than a Spanish townhouse.

Still, its first owner was a Spanish officer, and its builder was an American, Robert Jones. The hall-less floorplan here is important. It is three rooms wide and two rooms deep with cabinets and cabinet galleries, a derivative of French-Carribbean house types.

The oldest building in Louisiana and the Mississippi Valley is the stately Convent of the Ursulines at 1100 Chartres Street. Designed by a French-trained military engineer in 1745, it was completed in 1753. It resembles the Continental French buildings of the Louis XV period more than colonial institutions.

The façade we see from Chartres is the rear of the building, which faced the river and was surrounded by herbal gardens. The nuns used their herbs and potager to feed their staff, students, orphans, and soldiers whom they cared for in the neighboring military hospital.

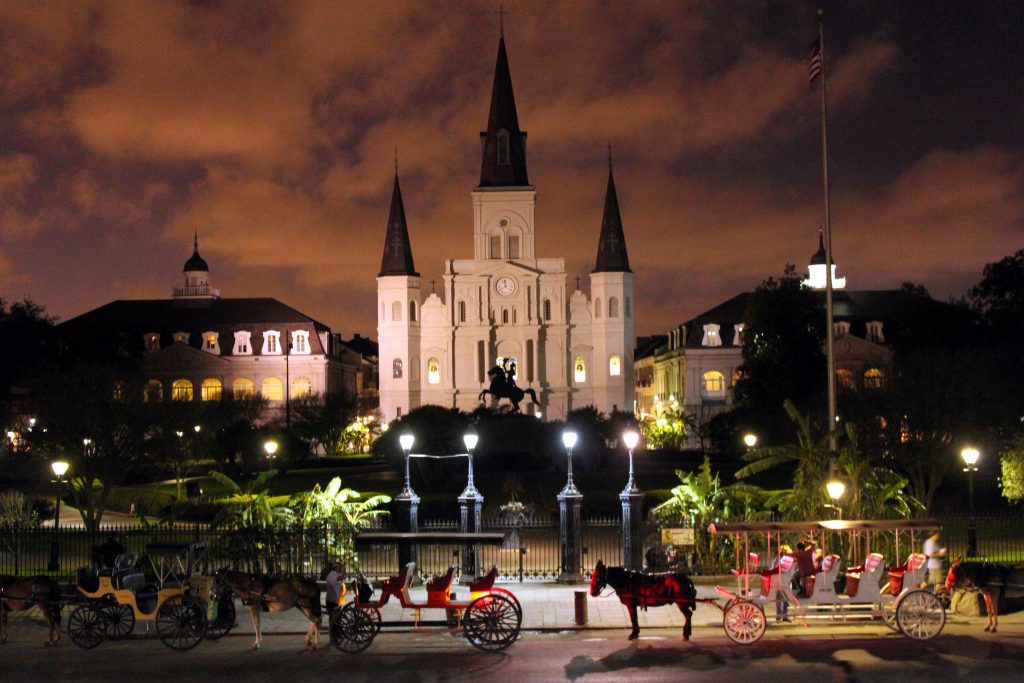

Jackson Square, the old Place d’Armes, is the oldest space in the city. Laid out with the town in 1718, it was always the parade grounds. The city began to make improvements to it in the 1830s, adding trees and walkways. The fence and equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson, hero of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, date to the 1850s.

If you’re planning a stay in New Orleans, be sure to check out our resource for French Quarter Hotels.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer, historian, translator, and archivist. She is known for her work in the New Orleans Notarial Archives as “Louisiana’s premier archivist” and her publications on New Orleans history.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Madame Pontalba’s Buildings

Jackson Square, and the land around it, was always for the use of the public, or so it seemed. There was the church (St. Louis Cathedral), the priests’ house (The Presbytere), and the town hall with the prison (The Cabildo). There was the square itself, with its parade ground, and the view of the Mississippi River. The idea of flanking the sides with important buildings was a natural one. The French put the governor’s house there, along with one for the top administrator, the intendant.

Today, the church and the old government buildings are standing in their current incarnations, but flanked on the sides by the stately and privately-built Pontalba Buildings. In 1849, Baroness Pontalba came home from France to her native city to build them on land she inherited.

Somehow, years earlier, the Spanish crown had allowed her father, the notary Almonester, to acquire the lots where the governor’s house had once opened to French-style gardens. In later years, long rows of military barracks succeeded them.

But by 1780, Almonester had two rows of rental properties on them, the base of a fortune in real estate. When the town burned down some years later, he had the wealth to design and reconstruct the church and The Cabildo, especially after he raised rents in the fire-devastated section.

After his death in 1798 his widow, reluctantly, made good on his earlier promise to rebuild The Presbytere also. And so it was that Madame Pontalba’s father before her had shaped the appearance of the public square. In her own time, she would meet the challenge of what was by then a family tradition.

Baroness, a strong-willed designer and a shrewd businesswoman

The Baroness was both a designer and a businesswoman. Would the council relinquish the sidewalk to erect colonnades to render that portion of our city pleasant in all seasons? The design is upon the Palais Royal and the Place des Vosges of Paris! And would the council agree to a tax break for 20 years in light of our expenses in this project, in which we beautify our city?

In an age when houses took six months to complete, the Pontalba buildings were a dozen years in planning and two years in construction. Begun in the spring of 1849, they were not finally finished until the winter of 1851. The Baroness had hired and fired the finest architects of the community, used their plans, then altered the product to her liking.

The result was an amalgam of Creole, Parisian, and Greek Revival tastes and uses. A melange, perhaps, but a reflection of the sophisticated preferences of their creator.

32 stately rowhouses, 16 on each side

The buildings are rowhouses, 32 of them, 16 to the side, each with three stories and an attic. If the outsides with their cast-iron galleries are French and American, the floor plans are Creole.

There are stores downstairs and doors leading to passageways instead of stair halls. At the end of these strange dark passageways, stairs curve gently to the second and third floors and the privacy of residences.

Downstairs, a walkway shelters customers. It is that way because Creoles liked to live upstairs on the second and third floors — the premiere and deuxième étages — and because Madame the Baroness Pontalba wanted it that way.

Elegant Pontalbas spurred the development of Jackson Square

In response to her plans, the council began its own building program. The Cabildo and The Presbytere soon had third-floor, French-style Mansard roofs like those in 19th-century Paris. Churchwardens let a major contract with the architect de Pouilly to rebuild the cathedral.

The council then had the city surveyor design and build the iron fence around the square and redo the inside landscaping. The Andrew Jackson Monument Association gathered funds to erect an equestrian statue of their hero. By the middle 1850s, Jackson Square was in the form it has had for parts of three centuries, substantially unchanged.

Today, the Pontalba buildings are owned by the city and the state, as gifts of its citizens. There are still stores below and residences over them. And tenants carry groceries down the long narrow passageways to the gently curving staircases leading to the upper floors.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer, historian, translator, and archivist. She is known for her work in the New Orleans Notarial Archives as “Louisiana’s premier archivist” and her publications on New Orleans history.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

The Best Live Music Clubs in the French Quarter

Image courtesy of Jeff Shewan

The live music scene in the French Quarter is a feast with many courses, and one that caters to many different appetites.

Looking for Dixieland jazz? Got it. Want to hear Cajun and zydeco rhythms? They come direct from the bayous to Bourbon Street nightly. Maybe you can’t make up your mind between rocking out at a club or cooling down with an intimate acoustic set. Don’t choose — you can easily walk from one venue to another to enjoy a variety of music in one evening.

What follows is a primer on some of the top venues delivering this nightly musical cornucopia.

Buffa’s

1001 Esplanade Ave.

Although it’s technically just past the Quarter in the Marigny, Buffa’s has long been a character-laden outpost of great New Orleans music. The lineup here can range from soulful jazz crooners to piano masters stroking the ivories. It helps that the bartenders pour strong drinks and the food is great. Buffa’s is also open late, till 2 am Sundays through Thursdays and till 4 am on Fridays and Saturdays.

Dragon’s Den

435 Esplanade Ave.

The eclectic variety of music hosted by the two-story Dragon’s Den matches the exotic setting in this singular club. Located at the edge of the Quarter, the intimate space creates a seductive atmosphere with lustrous red hues, Far East décor, a courtyard, and a wrought iron balcony over the tree-lined Esplanade Avenue. Look for all manner of music and a young, very local crowd.

Kerry Irish Pub

331 Decatur St.

It lives up to its Celtic billing with some of the best-poured Guinness stout in town and a welcoming atmosphere. There’s no cover charge for the nightly live music, which includes traditional Irish, alternative country, bluegrass, and rock.

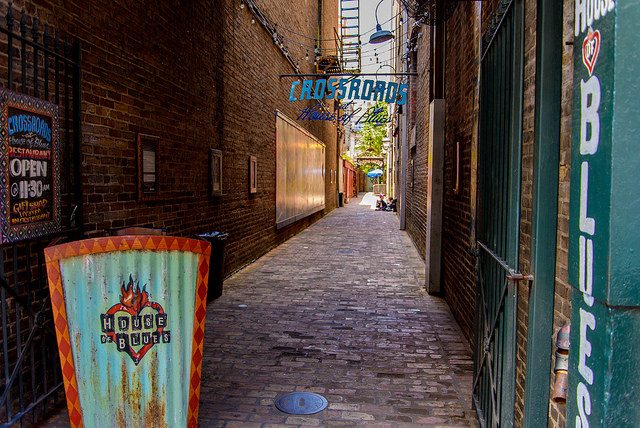

House of Blues

225 Decatur St.

The highly successful House of Blues opened its New Orleans venue over a decade ago, and it has grown into the French Quarter destination to hear nationally touring acts. In addition to the main stage, the club often has music in its restaurant or patio bar, as well as the more intimate concert hall in the adjacent House of Blues Parish, which hosts many local performers.

One Eyed Jacks

1104 Decatur St.

One Eyed Jacks, a popular live music venue formerly located at 615 Toulouse Street, reopened for Mardi Gras 2022 in the space that was formerly occupied by Jimmy Buffet’s Margaritaville and B.B. King’s Blues Club. One Eyed Jacks’ stage is big enough for touring rock bands and even 1950s-style burlesque shows, and the music lineup is as electric and eclectic as ever.

Are you planning to spend some time in New Orleans soon? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

The Crescent City Coffee Connection: History and Heritage Imbues Each Cup

History seekers can find a handful of monuments and memorials to the Civil War around New Orleans’ parks, museums and public spaces, but to experience one enduring local legacy of the conflict you need only order a cup of coffee. That would be coffee with chicory, to be more precise.

The Union naval blockade of the port of New Orleans during the war led to a sudden scarcity of many commodities, including coffee. So just as the French did during the blockades of the Napoleonic wars, resourceful New Orleanians stretched their precious stock of imported coffee by mixing it with the ground, roasted chicory root, which they could grow locally. Though an invention of wartime necessity, the chicory blend was embraced for the mellow caramel undertones and smooth texture it added to coffee.

Today, coffee with chicory remains the most popular blend in a city where people do not take the matter lightly. Thanks to the gourmet coffee chains sprouting up across the national landscape, much of America is waking up to the idea that coffee can be a real pleasure. But coffee has always been serious business in New Orleans — whether stacked in pyramids of 100-pound sacks on the port docks or served in china in the city’s finest Creole restaurants.

By the 19th century, New Orleans was already one of the world’s busiest ports and, thanks to its proximity to Latin America, coffee was one of its leading imports. Naturally, coffeehouses sprang up around the city. In fact, one city directory from the 1850s lists more than 500 coffeehouses in the rapidly growing port town.

Today, one-third of all coffee imported to North America lands first in New Orleans, according to research from the economic development group Greater New Orleans, Inc. A dozen local coffee roasters prepare products for over 20 national and local brands, while Folgers now operates the world’s largest coffee roasting plant a few miles downriver from the French Quarter. The heady aroma of roasting coffee is a familiar scent in the mornings in many of New Orleans’ historic neighborhoods.

Creole Coffee and “French Doughnuts”

While the vitality of the local coffee industry may be gauged by the ton, true coffee culture in New Orleans is measured one cup at a time at the city’s historic and modern coffeehouses and restaurants.

The quintessential New Orleans coffee experience is offered around the clock at Cafe Du Monde (1039 Decatur St.). A fixture in the French Market since 1862, Cafe Du Monde has about as much in common with the modern type of coffeehouse as the French Quarter itself does with a suburban strip mall.

A crowd as varied as limo-hopping debutantes, drag queens in full regalia, and small-town church youth groups now regularly crowd the bustling, open-air coffee stand. Don’t look for fancy espresso concoctions here; the standard order is café au lait (equal portions of coffee with chicory and steamed milk) and beignets, the fried squares of dough often called French doughnuts. The landmark coffee stand closes only for Christmas or when the occasional hurricane looks particularly menacing.

Cafe Du Monde once dueled for coffee supremacy in the French Market with the Morning Call Coffee Stand. Founded in 1871, it offered an almost identical menu of café au lait and beignets right around the corner from Café du Monde. However, the Morning Call has been serving more recent generations from its location at 5101 Canal Street (where New Orleans meets Lakeview; and it’s also the end of the line for a few bus routes and the Canal streetcar line).

While tradition is revered in the Crescent City, time hasn’t stood still for other incarnations of the New Orleans coffeehouse, and the French Quarter offers many different takes on the experience. The French Quarter outpost of CC’s Coffee House (941 Royal St.), for instance, combines the heritage of this long-time Louisiana coffee roaster with all the menu options and design elements of the much larger gourmet coffee chains.

Coffeehouses in the French Quarter are numerous and as varied as the people you see on the always colorful streets. From the polished brass and woodwork of the sunny Cafe Envie (1241 Decatur St.) to the charming, old-world Croissant D’Or Patisserie (617 Ursulines St.), these coffeehouses are united by New Orleans’ universal demand for quality coffee and the rich heritage that accompanies the brew here.

Are you planning to spend some time in New Orleans soon? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

The Dark Side of the French Quarter

Throughout its history, the French Quarter has all but sounded a siren’s call to extreme personalities. Depending upon what drives them, they may lob off the heads of chickens and invoke mysterious spirits while chanting and dancing around a burning fire like Marie Laveau or brutally mutilate and torture those in their non-paid “employ,” like Delphine LaLaurie.

Add physical drama in the form of elaborate above ground tombs, secret passageways, courtyards, and imposing aged mansions — and you have the French Quarter’s Dark Side.

Photo courtesy by Reading Tom

Haunted French Quarter: LaLaurie Mansion

The story of Delphine LaLaurie and the heinous manner in which she tortured slaves is probably the most widely known of the French Quarter’s macabre tales.

Madame LaLaurie, a respected socialite, hosted many a grand event at her opulent home at 1140 Royal Street. Mistreatment of slaves was illegal and society began to shun LaLaurie after a neighbor witnessed the elegant woman chasing a young servant girl with a whip. The neighbor saw the girl leap to her death from the roof in her efforts to avoid LaLaurie. The neighbor summoned the authorities and that was the end of LaLaurie’s social career.

Upon her arrest, authorities removed the slaves from LaLaurie’s home. A short time later, a fire broke out in the kitchen. In their efforts to thwart the fire, neighbors and firefighters stumbled upon a grisly torture chamber in the attic. Nude slaves, most of them dead, were discovered. Some were chained to the walls, some were strapped to makeshift operating tables, and others were confined in cages made for animals. They had undergone various elaborate forms of torture and mutilation.

When news of the findings was published in the local newspaper, an angry mob drove LaLaurie and her family from the city.

Reports that the house is haunted have been rampant ever since. Many have claimed to hear screams of agony coming from the empty house. Others have seen apparitions of slaves walking about the property. There have even been reports of people claiming to have been attacked by an angry slave in chains.

Though the house has changed hands numerous times and has not served as only a private home, but also a musical conservatory, a school for young women and a saloon, among other things, many of the building’s owners have experienced some form of misery or another associated with the house.

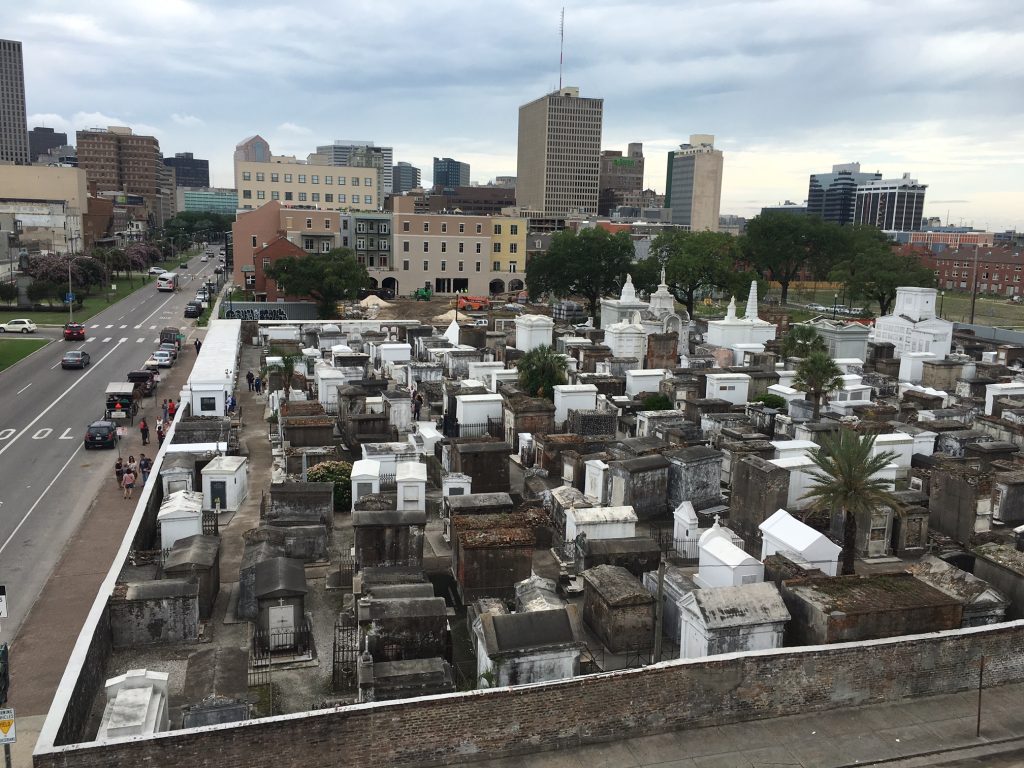

St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and Marie Laveau

Both her life and her burial place have long evoked interest in Marie Laveau, New Orleans’ undisputed Queen of Voodoo, who is buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, the city’s oldest burial ground.

The waterlogged, swampy soil upon which New Orleans is built makes digging more than a couple of feet impractical, especially if the reason for digging is a burial of anything more substantial than a hamster. This gruesome revelation was made soon after the city’s first cemetery was established on St. Peter Street, just inside the current French Quarter. Graves started popping to the surface and bodies floated down the street when it flooded — which was often.

The solution was to avoid burial altogether and house the dead in above-ground tombs. In the mid-1800s, the site of hundreds of little marble, granite or stone “houses” led to the coining of the term “cities of the dead.”

St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 was established by the Spanish in 1789. In addition to Laveau, many of the city’s first occupants and most notorious personalities are entombed here, including Etienne de Bore, father of the sugar industry, and Homer Plessy, of the Plessy v. Ferguson 1892 Supreme Court decision establishing separate but equal Jim Crow laws for African-Americans and whites in the South.

The tombs here are of whitewashed, stucco-covered red brick, and shine with an eerie brilliance in the gloom of evening as well as the midday sun.

It’s easy to find Laveau’s tomb. Many small red Xs cover its surface, signs that visitors have made a wish in the hope of obtaining Laveau’s assistance. The faithful also leave behind offerings of coins, herbs, beans, bones, bags, flowers, and other tokens in hopes of invoking her goodwill.

Some believe Laveau materializes annually to lead the faithful in worship on St. John’s Eve. The ghost is always recognizable, they say, thanks to the knotted handkerchief she wears around her neck. A man once claimed to have been slapped by her while walking past her tomb. It is also said that Laveau’s former home at 1020 St. Ann Street is also among the French Quarter’s many haunted locales. Believers claim to have seen her spirit, accompanied by those of her followers, engaged in Voodoo ceremonies there.

Are you planning to spend some time in New Orleans soon? To stay close to all the action, book a historic boutique hotel in the French Quarter at FrenchQuarter.com/hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Best Bars in the French Quarter

Photo courtesy of The Bombay Club on Facebook

The numbers don’t lie: According to numerous studies, New Orleans is permanently wedged on the list of top cities that have the most bars per capita in the nation. And according to our unofficial calculation, the lion’s share of those bars is concentrated in the French Quarter. With watering holes of every type and persuasion harkening from the corners, alleys and thoroughfares of the Vieux Carre, how is one to choose the best drinking option?

We’ve narrowed down the selection to standout bars in a few categories. Choose your favorite and check it out… or get a drink to go and hit up several.

Jazz club: The Bombay Club

830 Conti Street

Let’s face it: You came to New Orleans to hear great music, eat great food, and drink — and in this old-school jazz and blues club, you can accomplish all three. Settle yourself into a curtained booth or deep leather chair, order a classic martini and charred hanger steak, and savor the smooth sounds of trad jazz.

Dive bar: Aunt Tiki’s

1207 Decatur Street

You know you’ve spent too long at this 24-hour bar when morning light begins to filter through the dirty plastic strips that serve as a door. But it’s an easy mistake to make when the bartenders pour heavily and the Halloween decoration-filled interior is dark as night. You won’t meet many fellow tourists in this cash-only joint, but you will find cheap drinks and a good time. (P.S. Contrary to what the name may suggest, Aunt Tiki’s is definitely not a tiki bar.)

Gay bar: Oz

800 Bourbon Street

If you’re looking to dance, take in a drag show, and unwind in a LGBTQIA+-friendly space, walk past the strip clubs and three-for-one beer stands until you arrive at this two-story dance mecca. If the dance floor gets too packed for your liking, head to the second-floor balcony for some air and quality people-watching.

Photo courtesy of Beachbum Berry’s Latitude 29 on Facebook

Tiki bar: Beachbum Berry’s Latitude 29

329 N. Peters Street

In a nutshell, Latitude 29 is a Tiki-style gastropub serving up exotic drinks and island-inspired cuisine such as pineapple bread. The menu for both drinks and food isn’t extensive, but everything is done well. The drinks range from the classics like Mai Tai to the inventively named in-house creations. The food matches the cocktails, offering sticky ribs, Filipino-style egg rolls, pimento cheese rangoons, and chickpea curry.

Photo courtesy of Molly’s at the Market on Facebook

Irish pub: Molly’s at the Market

1107 Decatur Street

Located on lower Decatur Street, steps from Frenchmen Street’s nightlife, Molly’s on the Market serves as an ideal jumping-off point for the evening. With old signs, T-shirts, newspaper clippings, and other paraphernalia on the walls, it has the lived-in feel of a longtime neighborhood hang. Try the frozen Irish coffee, but don’t expect a fancy craft cocktail here. Molly’s is a beer-and-a-shot type joint.

Craft cocktails: Bar Tonique

820 N. Rampart Street

Located on N. Rampart Street, right on the streetcar line, Tonique, is a candlelit, intimate place to canoodle with a date over beautifully constructed craft cocktails. There’s also a thoughtful mocktail menu in the weathered, brick-walled bar. On a pretty day, there’s nothing nicer than getting the second round to go and drink it in leafy Armstrong Park, which is right across the street.

The Grand Dame: French 75

813 Bienville Street

Well, we can’t leave out French 75 from our roundup of great cocktail bars, considering this is a bar that is, hey, named for a cocktail (although interestingly, the French 75 was not invented here — that honor goes to Paris, France). French 75 is located inside Arnaud’s Restaurant and has a fantastic cocktail list that includes both New Orleans classics and some fruit-inspired goodness — the perfect compliment to a hot New Orleans day. There’s also an elegant small-place bar menu with French items like escargot and the restaurant’s signature shrimp Arnaud.

The interior of the bar is as lovely as the drinks that come out of it — this is a true grand dame New Orleans institution, accented in dark woods and elegant furniture such that you feel as if you’re drinking in a particularly well-appointed parlor.

Romantic: Sylvain

625 Chartres Street

Sylvain sells itself as a gastropub, and while the food is excellent, we don’t want to ignore the excellent drinks that are prepared behind the bar. It helps, of course, that Sylvain has an absolutely lovely courtyard, and did we mention the food? Because nothing compliments your drink like their New American rustic fare. Oh, they also serve “fried and champagne” — a bottle of champagne and hand-cut fries — which is just perfect.

Great for Groups: Black Penny

700 N. Rampart Street

If you’ve got a big group of friends and need a chill bar to sink beer and cocktails, it’s hard to do better than the Penny, which sets at the edge of the Quarter. It’s a good alternative to some of the, shall we say, louder large bars along Bourbon Street — no volume-splitting karaoke happening here.

It’s also notable for both friendly bartenders, good prices, strong drinks, and a fantastic selection of craft beer (most of which is served by the can). Unlike a lot of Quarter bars, the Penny is pretty spacious, so you’ve got room to mingle, but there are booths and seating for those who want to make a more intimate night of it. Worth noting: This spot also happens to have excellent top-shelf scotch, and is publicly and loudly LGBTQIA+-friendly.

Iconic: The Carousel Bar & Lounge

214 Royal Street

One of the most iconic of New Orleans bars, the Carousel sits at the excellent intersection of old-school elegance and off-the-wall quirk, which is a description that could really be applied across the whole of New Orleans, now that we think about it. The bar, which includes a piano lounge, is in fact a 25-seat merry-go-round, so hold on to your seat as you hold onto your drink. We’re kidding — the bar doesn’t spin particularly fast, although if you’ve had a few of their stronger libations, you might start feeling dizzy.

Don’t miss out on all the excitement the French Quarter has to offer all year round, round the clock! Book your room at any of these historic hotels today!

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

History of the French Quarter

Founded as a military-style grid of seventy squares in 1718 by French Canadian naval officer Jean Baptiste Bienville, the French Quarter of New Orleans has charted a course of urbanism for parts of four centuries. Bienville served as governor for financier John Law’s Company of the Indies, which in naming the city for the Regent Duc d’Orleans sought to curry Court favor before failing spectacularly in the “Great Mississippi Bubble.”

The French Period legacy endures in the town plan and central square, the church of St. Louis, the Ursuline Convent and women’s education, the old-regime street names such as Bourbon and Royal, the charity hospital, and a mixed legacy of Creole culture, Mardi Gras, and the important effects of African enslavement combined with a tolerant approach to free persons of color.

The “Spanish” Quarter

In 1762, the indifferent Louis XV transferred Louisiana to his Bourbon cousin Charles III of Spain. Emboldened by a period of Spanish vacillation in taking power, Francophile colonists staged a revolution in 1768, summarily squelched by Alejandro O’Reilly with a firing squad at the Esplanade fort.

Spanish rule lasted for four decades, imparting a legacy of semi-fortified streetscapes, common-wall plastered brick houses, and walled courtyards used as gardens and utility spaces with separate servants’ quarters and kitchens. Olive oil cooking and graceful wrought iron balconies, hinges and locks in curvilinear shapes, and strong vestiges of civil law remain from the Spanish presence.

After the great fires of 1788 and 1794, The Cabildo, or town hall, The Presbytere, or priests’ residence, and ironically named “French” Market arose to take a permanent place in French Quarter history.

After the Louisiana Purchase

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase, signed within the elegant salon of the Cabildo, transferred the colony to the United States, inaugurating an era of prosperity. American culture made slow inroads, largely owing to the arrival of 10,000 refugees from the French and Haitian Revolutions and Napoleonic wars.

The “glorious victory” of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, led by Indian fighter and future president Andrew Jackson over numerically superior British forces, fixed loyalty to the American nation. The French Quarter’s golden era followed as cotton, sugar and steamboats poured into the city. American, Irish, German, African, and “Foreign French” immigrants swelled the population, creating a heterogeneous matrix of culture, language, religion, and cuisine.

Civil War to WPA

Civil War and Reconstruction, played out politically on the streets of the French Quarter, put an end to prosperity and inaugurated a tug of war between reform and machine factions as the Old Square declined. Creoles moved to Esplanade and later Uptown, and famine-driven Sicilian immigrants found cramped lodging in the grand spaces of French Quarter mansions of the 1890s.

The birth of jazz in the 1900s in nearby Storyville nurtured musical legends Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong, Buddy Bolden, King Oliver, Bunk Johnson, Nick LaRocca, and other jazz and ragtime greats.

By 1920, the legacy of a storied past first celebrated by George Washington Cable and Lafcadio Hearn in the 1880s attracted writers and artists in increasing numbers. William Faulkner, Sherwood Anderson, Tennessee Williams, and Truman Capote were among American writers attracted to the French Quarter for its freewheeling urbanism, quaint surroundings and creative stimulus, even as the building stock declined.

The Vieux Carré Commission

Nineteen thirty-six marked the onset of regulatory controls in the form of the state-sanctioned Vieux Carré Commission. Residents dug in to preserve the quaint and distinctive character of the old Quarter as art galleries and antique stores sprouted on Royal Street and brassy Dixieland-style jazz flourished in Bourbon Street nightclubs and strip joints.

By 1960, with traditional jazz in decline, Preservation Hall emerged to serve beleaguered musicians. Here Sweet Emma Barrett and other traditional and largely African-American musicians found appreciative and sober audiences. Today, these and other preservation battles are the order of the day as increasing pressure from a tourist-driven economy lures some 10 million visitors annually to the time and foot-worn streets of the Vieux Carré.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer, historian, translator, and archivist. She is known for her work in the New Orleans Notarial Archives as “Louisiana’s premier archivist” and her publications on New Orleans history.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

Searching for Laffite the Pirate

Jean Laffite “The Corsair” by E.H. Suydam

Laffite the pirate, a curious fellow, has been evading the establishment. If once he escaped the sheriff, today he still eludes the historical authorities.

Who was the real Jean Laffite? Was he born in the former colony of St. Domingue or in the cities of Bayonne or Bordeaux? Did he die still practicing his trade as a pirate in the Yucatan in the middle 1820s or as a middle-class American citizen of the 1850s?

Should we judge him a cutthroat pirate, a patriotic privateer, or a gentleman rover? Why did he return to pirating after he received a pardon from President Madison for his support of Americans in the Battle of New Orleans? Why did he spy for Spain after the War of 1812 was over, when he claimed that his aim had always been to punish the Spanish for their cruelties? Did he really have a Jewish grandmother anyway, whom the Spanish persecuted?

Did he have a blacksmith shop on Bourbon Street? If so, where is a scrap of evidence connecting that famous tavern to him? What about his journal, now at the archives in Liberty, Texas? Is it real? Was it his or some other fellow’s of the 1840s? In it, the writer claims to love the downtrodden, hate the Spanish, respect the Declaration of Independence, and have contempt for the English. If Jean Laffite loved the downtrodden so keenly, why did he make a living smuggling slaves into America after Congress had prohibited their importation?

What can we all agree upon, or almost? He burst on the scene in the Gulf of Mexico about 1803, preying on shipping and selling smuggled slaves and merchandise from the swamps of Barataria. He thumbed his nose at the governor, “parading arm-in-arm on the streets of New Orleans with his buddies.”

The crafty lawyers Livingston and Grymes always managed to get his people out of jail when arrested for piracy. Laffite’s older brother Pierre sold slaves openly through notaries in New Orleans, but was jailed in 1814. He spent the summer in chains in the heat of the Calaboose on what would later be Jackson Square.

Dominique You and Renato Beluche were his compatriots in what German merchant Vincent Nolte described as a “colony of pirates” infesting the shores of Louisiana. They were all surprised by federal agents in September 1814 at Grand Terre island.

Not long later, Laffite turned down an offer from a British navy captain to join the Limeys in the ongoing War of 1812. Instead, he offered his troops to Governor William Claiborne, received a huffed refusal, and ended up being welcomed into the rag-tag American army by Andrew Jackson.

For the great Battle of January 8, 1815, he provided the flints and the gunpowder from his stolen stores in Barataria. With Jackson’s Kentuckians, his marksmen helped to trounce the advancing British army on that wintry battle morning. Armed with a pardon for his whole company, Laffite walked the streets of New Orleans a free man for a year or so afterward.

But law-abiding was not to his liking. He left the city to found a community of smugglers at Galveston and a new base for “privateering.” After the federal government got serious and blew him out of Galveston, he turned to the Yucatan and was never heard from again after the middle 1820s.

That is, until his “journal” surfaced. Uncannily authentic-looking, on genuine century-old paper, and written by a person who knew all the players, it surfaced in the 1940s. Its author had it in for the Spanish, mentioned all the right people, and had the right signature. He also spelled the name correctly, with two “F’s” and only one “T.”

Purportedly, Laffite had lived until the 1850s and died as a prosperous middle-class citizen with traceable posterity. The journal turned up with family papers in a trunk inherited by a purported descendant of an apparently parallel character.

For 50 years the “Journal of Jean Laffite” has stirred controversy worthy of its subject. Transcribed, translated from the French, and issued twice, it has writers scrambling to deal with its substance as well as its provenance. The persona that emerges from its pages is a moralistic, inwardly-focused paranoid with perfect recall of names and events and complete ignorance of his own failings.

This Laffite is not the suave gentleman depicted by historians. And yet they sensed from the beginning that there was something in the person in addition to a pirate.

Writers have been penning their thoughts on Laffite since the 1820s. A biographer of the 1950s claimed that he had so much evidence that no further work would be needed. Since that moment, eight more Laffite biographies have been published. And counting.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer, historian, translator, and archivist. She is known for her work in the New Orleans Notarial Archives as “Louisiana’s premier archivist” and her publications on New Orleans history.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

The Many Lives of the Steamboats Natchez

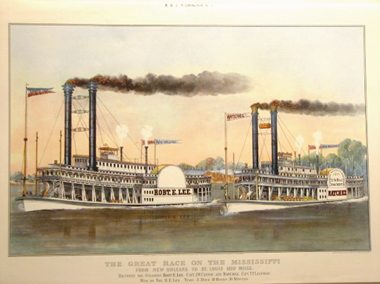

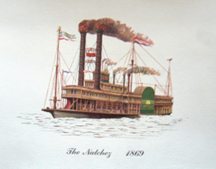

Top to bottom: The first-ever Natchez, built in 1823. The 206-ton fledgling made history in 1825 transporting General Lafayette through the Mississippi Valley.

The Natchez of racing fame, built in 1869. A colossal gamble to preserve the steamboat freight buisiness, it was not the most elegant of the Leathers’ seven steamboats.

Currier and Ives’ iconic Great Race on the Mississippi from New Orleans to St. Louis/ 1210 Miles bet. the Steamers Robt. E. Lee, Capt. JW Cannon, and Natchez, Capt. T.P. Leathers is history’s most famous steamboat image. Commemorating the bally-hooed 1870 match race between riverboat titans, the print shows the boats pouring telltale clouds of fiery smoke from towering stacks.

With bettors from as far away as Europe waiting for the outcome, Captain Cannon of the Lee won the race some three hours faster than his rival. Leathers had refused to limit passengers or strip his boat, insisting ever after that the Natchez was faster.

Whoever the winner, in many ways the international attention to steamboat speed was as important as the race results. For the real struggle was less between high-profile steamboats than between the steamboat and its destiny, between the survival of steamboats facing railroad competition.

That a boat could make it to St. Louis in fewer than four whole days was a widespread notice of a fast-paced capacity to deliver cotton, rice, corn, and coal downstream and manufactures upstream.

Both the Lee and the Natchez were high-stakes gambles by the most experienced steamboat men in history. Falling into a particular niche in transportation history, they were built at enormous expense in the teeth of the depressive post-Civil War years while railroads completed tracks from New Orleans to Chicago.

The Lee, Natchez and such leviathans as the 313-foot J.M. White, the 335-foot Great Republic, and the 255-foot Frank Pargoud, were designed to carry unprecedented volumes of freight at a competitive rate of speed. Their better-known, extravagant, paneled, and gilded passenger accommodations were a luxurious extra.

They were in a different class altogether from the workaday pre-war steamboat. For all their enduring fame, the racing Lee and Natchez were atypical to steamboat history. They were colossal bluffs that, for a time, worked.

The Natchez was the eighth of 12 steamboats to carry the name and one of seven built for the legendary Thomas P. Leathers (1820-1896). The Kentucky-born captain was not, however, the first to name a boat The Natchez. That honor goes to a 206-ton fledgling that made history in 1825 carrying Revolutionary War hero General Lafayette on his triumphal tour of the American heartland. A more ambitious, 792-ton Natchez succeeded it in 1838, only to be lost in an 1842 collision.

Leathers had his first-ever Natchez built in 1846 for the New Orleans to Vicksburg cotton trade. He built his second in 1849, and his third just four years later as a packet vessel departing New Orleans every Saturday afternoon.

After only six weeks of service, the boat was consumed in the great New Orleans wharf fire of February 1853. Of the three lives lost, one was Leathers’ brother James. Undefeated by tragedy and the short life expectations of his steamboats (they lasted an average of just over seven years), Leathers built them bigger and better, all for the New Orleans-Vicksburg trade.

He built his fifth in 1855; the sixth just five years later. After Natchez No. 6 burned in the Civil War, he was back in 1869 to build the boat of racing fame. At 1547 tons, it was over seven times more massive than his first. It ended up scrapped after putting in a decade of service. Leathers’ final Natchez lasted from 1879 to 1887, when he left the river with it.

At 67 and nationally famous, Leathers was ready to retire to his elegant 1859 Garden District mansion, where he lived alternately with a home in Natchez, “Myrtle Terrace.” (Both houses still stand.) Unfortunately, a bicycle hit and killed him on St. Charles Avenue.

His son and daughter-in-law, the path-breaking female captain Blanche D. Leathers, succeeded him with the Natchez No. 10. Built in Jeffersonville, Indiana in 1891, it was not dismantled until 1918 after Mrs. Leathers’ long and compelling career. One more Natchez would follow before the current boat was begun in 1975.

The last of the steamboats Natchez was built in Plaquemine Parish for Wilbur Dow and the New Orleans Steamboat Co. With 1925 oil-burning engines from the stream tow Clairton, the 236-foot boat is all steel. Her first captain was New Orleans’ own Clarke C. “Doc” Hawley. She is a regular in the harbor of New Orleans.

Steamboats Natchez played a salient part in the greatest moments of river history. They were born in the years of the small-scale, 200-ton side wheeler operating with no set schedule or itinerary. Coming to life again as the 1840s packet boat, they operated with regular departures, fixed destinations, and reliable returns.

The early boats had cramped and narrow cabins divided by curtains and meals on common tables that passengers provisioned themselves from shore-side merchants. Later Natchez steamboats had sumptuous gilded-era “stateroom” interiors with lavish, seven-course meals accompanied by a dozen wines.

If the most well-known Natchez was the boat of racing fame, it was not the most elegant. That honor goes to T. P. Leathers’ seventh and final vessel of 1879, with its 100 cabin transoms picturing Native American chiefs and its 34-cylinder engines.

The Natchez name lived on in the early 20th century with the triumph of Blanche Leathers as the river’s most famous female captain. When the steamboat ended up in the excursion business, the Natchez came to life again as today’s elegant harbor cruiser. Its hoarse whistle across the port of New Orleans reminds us daily of the glory of the steamboat age.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer, historian, translator, and archivist. She is known for her work in the New Orleans Notarial Archives as “Louisiana’s premier archivist” and her publications on New Orleans history.

Image credits (top to bottom): Donald T. Wright/Joseph Merrick Jones Steamboat Collection, Manuscripts Department, Tulane University Libraries Courtesy Tulane University Special Collections.

Related Articles

JOIN THE NEWSLETTER!

First Notes: New Orleans and the Early Roots of Jazz

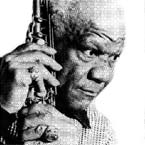

Top to bottom: Buddy Bolden, Sidney Bechet, Bunk Johnson

New Orleans has always been different, complex and intriguing, so it’s fitting that jazz, the musical style the city created and gave to the world, should follow the same tune.

Jazz is a byproduct of the unique cultural environment found in New Orleans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the vestiges of French and Spanish colonial roots, the resilience of African influences after the slavery era and the influx of immigrants from Europe. The ways these cultures mingled, collided and evolved together in the Crescent City produced America’s most distinctive musical style.

From the French Opera House to Congo Square

One of the key components to the birth of jazz was New Orleans’ long and deep commitment to music and dance, says Bruce Raeburn, a jazz historian and curator of the Hogan Jazz Archives at Tulane University. The city was home to the first opera house in North America, for instance, and many of the rich musical traditions of Europe were embraced and celebrated here going back to the city’s early colonial days.

Long before jazz was established, musical events were part of the social fabric of the city, from formal balls where European dances competed for the public’s attention with more exotic sounds migrating north from Latin America to the marching bands that comforted mourners after funerals.

Another element driving this musical heritage toward the creation of jazz gets down to race and the distinctive black experience in New Orleans. Though the city was a leading slave port and segregation persisted long after slavery was abolished, people of different races mixed much more freely in New Orleans than in other American cities.

“There were opportunities for interaction, in spite of segregation, and many neighborhoods were a crazy quilt with blacks, whites and Creoles living together,” says Raeburn.

New Orleans is not your typical American city

Raeburn points out that while the rest of the antebellum South was trying to stamp out any remnants of African culture slaves might cling to, New Orleans’ city fathers tried to regulate it, allowing at least a small venue for traditions to continue and evolve. For instance, slaves were allowed to congregate, make music and dance in Congo Square, an area that is today part of Louis Armstrong Park on North Rampart Street on the edge of the French Quarter.

“This was not your typical American city, there was much more of a Mediterranean mentality here,” Raeburn says.

In addition, New Orleans was home to the largest population of free people of color during the slavery era. Many of these people had access to European musical traditions, and in some cases formed the bands that played at the city’s balls and concerts.

To this cauldron, the waves of history added spiritual music from the church, the blues carried into town by rural guitar slingers, the minstrel shows inspired by plantation life, the beat and cadence of military marching bands, and finally the syncopation of the ragtime piano, America’s most popular music for a time in the early 20h century.

Sampling from and experimenting with all of these diverse influences, New Orleans musicians added the touchstone ingredient of improvisation to produce something completely new.

Jazz defied the then-dominant Western musical tradition of following a composer’s music precisely, and replaced it with a dedication only to following a feeling or emotion in music.

Top to bottom: Joe “King” Oliver, Kid Ory, Jelly Roll Morton

Buddy Bolden, Sidney Bechet, Bunk Johnson, Jellyroll Morton, Kid Ory, King Oliver…

Historians generally point to Buddy Bolden, a cornet player, as the first jazz musician. Beginning around 1895, he assembled a band that was popular at New Orleans street parades and dances and included musicians who would later become prominent figures in early jazz development, including Sidney Bechet and Bunk Johnson.

Bolden’s personal theme song was called “Funky Butt” and today the jazz club on North Rampart Street of the same name pays him tribute. He was followed by a long list of musicians who each left their stamp on the evolving style of jazz in the early part of the 20th century, including Joe “King” Oliver, Kid Ory and Jelly Roll Morton, generally considered the first great jazz composer.

Jazz diaspora

While rooted in New Orleans, the city’s jazz pioneers traveled extensively for work. This artistic diaspora was accelerated when the city’s official red light district, Storyville, was ordered closed by the federal government in 1917, thus shuttering the saloons and bordellos that had proved such reliable venues for early jazz musicians. Wherever the musicians went, they played, and the sound stuck, later evolving on its own into differentiated styles in Chicago, New York, Kansas City, and West Coast cities.

“The original jazz idiom started in New Orleans, and it spread,” says Raeburn. “As it spread, it changed, but the original sound came from New Orleans.”