The Many Lives of the Steamboats Natchez

Top to bottom: The first-ever Natchez, built in 1823. The 206-ton fledgling made history in 1825 transporting General Lafayette through the Mississippi Valley.

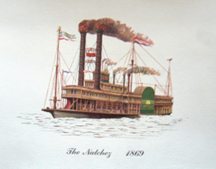

The Natchez of racing fame, built in 1869. A colossal gamble to preserve the steamboat freight buisiness, it was not the most elegant of the Leathers’ seven steamboats.

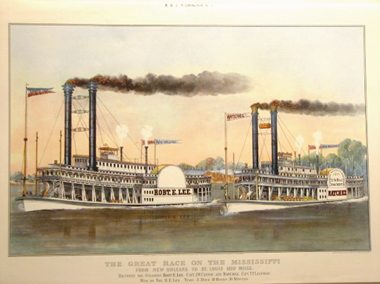

Currier and Ives’ iconic Great Race on the Mississippi from New Orleans to St. Louis/ 1210 Miles bet. the Steamers Robt. E. Lee, Capt. JW Cannon, and Natchez, Capt. T.P. Leathers is history’s most famous steamboat image. Commemorating the bally-hooed 1870 match race between riverboat titans, the print shows the boats pouring telltale clouds of fiery smoke from towering stacks.

With bettors from as far away as Europe waiting for the outcome, Captain Cannon of the Lee won the race some three hours faster than his rival. Leathers had refused to limit passengers or strip his boat, insisting ever after that the Natchez was faster.

Whoever the winner, in many ways the international attention to steamboat speed was as important as the race results. For the real struggle was less between high-profile steamboats than between the steamboat and its destiny, between the survival of steamboats facing railroad competition.

That a boat could make it to St. Louis in fewer than four whole days was a widespread notice of a fast-paced capacity to deliver cotton, rice, corn, and coal downstream and manufactures upstream.

Both the Lee and the Natchez were high-stakes gambles by the most experienced steamboat men in history. Falling into a particular niche in transportation history, they were built at enormous expense in the teeth of the depressive post-Civil War years while railroads completed tracks from New Orleans to Chicago.

The Lee, Natchez and such leviathans as the 313-foot J.M. White, the 335-foot Great Republic, and the 255-foot Frank Pargoud, were designed to carry unprecedented volumes of freight at a competitive rate of speed. Their better-known, extravagant, paneled, and gilded passenger accommodations were a luxurious extra.

They were in a different class altogether from the workaday pre-war steamboat. For all their enduring fame, the racing Lee and Natchez were atypical to steamboat history. They were colossal bluffs that, for a time, worked.

The Natchez was the eighth of 12 steamboats to carry the name and one of seven built for the legendary Thomas P. Leathers (1820-1896). The Kentucky-born captain was not, however, the first to name a boat The Natchez. That honor goes to a 206-ton fledgling that made history in 1825 carrying Revolutionary War hero General Lafayette on his triumphal tour of the American heartland. A more ambitious, 792-ton Natchez succeeded it in 1838, only to be lost in an 1842 collision.

Leathers had his first-ever Natchez built in 1846 for the New Orleans to Vicksburg cotton trade. He built his second in 1849, and his third just four years later as a packet vessel departing New Orleans every Saturday afternoon.

After only six weeks of service, the boat was consumed in the great New Orleans wharf fire of February 1853. Of the three lives lost, one was Leathers’ brother James. Undefeated by tragedy and the short life expectations of his steamboats (they lasted an average of just over seven years), Leathers built them bigger and better, all for the New Orleans-Vicksburg trade.

He built his fifth in 1855; the sixth just five years later. After Natchez No. 6 burned in the Civil War, he was back in 1869 to build the boat of racing fame. At 1547 tons, it was over seven times more massive than his first. It ended up scrapped after putting in a decade of service. Leathers’ final Natchez lasted from 1879 to 1887, when he left the river with it.

At 67 and nationally famous, Leathers was ready to retire to his elegant 1859 Garden District mansion, where he lived alternately with a home in Natchez, “Myrtle Terrace.” (Both houses still stand.) Unfortunately, a bicycle hit and killed him on St. Charles Avenue.

His son and daughter-in-law, the path-breaking female captain Blanche D. Leathers, succeeded him with the Natchez No. 10. Built in Jeffersonville, Indiana in 1891, it was not dismantled until 1918 after Mrs. Leathers’ long and compelling career. One more Natchez would follow before the current boat was begun in 1975.

The last of the steamboats Natchez was built in Plaquemine Parish for Wilbur Dow and the New Orleans Steamboat Co. With 1925 oil-burning engines from the stream tow Clairton, the 236-foot boat is all steel. Her first captain was New Orleans’ own Clarke C. “Doc” Hawley. She is a regular in the harbor of New Orleans.

Steamboats Natchez played a salient part in the greatest moments of river history. They were born in the years of the small-scale, 200-ton side wheeler operating with no set schedule or itinerary. Coming to life again as the 1840s packet boat, they operated with regular departures, fixed destinations, and reliable returns.

The early boats had cramped and narrow cabins divided by curtains and meals on common tables that passengers provisioned themselves from shore-side merchants. Later Natchez steamboats had sumptuous gilded-era “stateroom” interiors with lavish, seven-course meals accompanied by a dozen wines.

If the most well-known Natchez was the boat of racing fame, it was not the most elegant. That honor goes to T. P. Leathers’ seventh and final vessel of 1879, with its 100 cabin transoms picturing Native American chiefs and its 34-cylinder engines.

The Natchez name lived on in the early 20th century with the triumph of Blanche Leathers as the river’s most famous female captain. When the steamboat ended up in the excursion business, the Natchez came to life again as today’s elegant harbor cruiser. Its hoarse whistle across the port of New Orleans reminds us daily of the glory of the steamboat age.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer, historian, translator, and archivist. She is known for her work in the New Orleans Notarial Archives as “Louisiana’s premier archivist” and her publications on New Orleans history.

Image credits (top to bottom): Donald T. Wright/Joseph Merrick Jones Steamboat Collection, Manuscripts Department, Tulane University Libraries Courtesy Tulane University Special Collections.