Rubbing the Right Way: The Infectious Sounds and Long Evolution of Zydeco Music

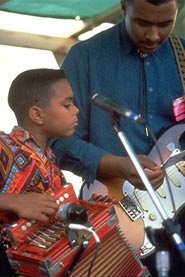

Louisiana Zydeco Musicians

It’s Thursday night at the Mid-City Lanes Rock ‘n’ Bowl (4133 S. Carrollton Ave., 504-482-3133), a vintage, second-floor bowling alley located near the geographic center of New Orleans. Bowlers are rolling strikes and gutter balls on the lanes, but the attention of most in the crowd tonight is focused on the stage. Thursday is zydeco night at Rock ‘n’ Bowl – which also functions as a music hall – and most of the people have come to dance. In a moment, the accordion, rubboard, drums and guitar ring from the stage, the singer begins hollering a mixture of Creole French and English lyrics about love and loss and the wooden floor fills once again with dancing couples.

Zydeco is as distinctive a component of Louisiana culture as crawfish, hot sauce and bayou landscapes, and like many things Louisianan, its colorful traditions and intricate history lend it a distinctive style among other genres of music.

At its essence, zydeco is the dance music of the black Creoles of southwest Louisiana and east Texas, says Michael Tisserand, whose book “The Kingdom of Zydeco” tells the story of the music and the communities that produced it. Though it started in the swampy bayou lands in the early part of the 20th century, it has exploded in popularity in the past few decades. It’s common to find zydeco festivals in California and the Northeast and Louisiana bands can now tour the world with their music.

“The reason for its enduring popularity at local dancehalls and at stages everywhere else is pretty obvious – it’s hard to stand still when you’re hearing great zydeco,” says Tisserand.

Sure enough, wherever a zydeco band is performing, feet begin moving, bodies begin swaying and couples come together for fast-paced dancing or slow-tempo waltzes. There is a dancing style universally called zydeco dancing, but the music is so infectious that people hearing it for the first time are often drawn to the dance floor to do their own thing.

Cajun or Zydeco?

One common point of confusion for visitors and new initiates to zydeco music is its relationship to Cajun music. Just as Cajun and Creole cooking are often equated, so too are Cajun music and zydeco often mistaken as two different names for the same thing. Like the cuisines, they do share much in common – most importantly the accordion that is so prominent in each genre – but each developed under its own set of influences and have unique sounds and styles. Cajun music comes primarily from the traditions of the French-speaking Cajuns who came to Louisiana from modern-day Nova Scotia, while zydeco music reflects the African-Caribbean roots of its players, Tisserand explains. The fiddle turns up in Cajun music while the rubboard (that corrugated metal plate that looks like an old fashioned laundry device) is a lead sound in zydeco. And while Cajun music has incorporated more stylings from country music, zydeco has picked up more of its own contemporary influences from blues and R&B.

“The histories of the two styles of music are deeply intertwined, and there are Cajun musicians who play zydeco, and zydeco musicians who play Cajun. Basically, you just can’t tell a musician what they can and can’t play,” Tisserand says. “Face it, it’s Louisiana, and everything’s all mixed up together in the most wonderful of ways.”

The word “zydeco” has its own colorful history. It is derived from les haricots, French for beans. One commonly cited explanation for the evolution of the word goes back to a Creole expression: “les haricots sont pas sales,” or “the beans aren’t salty” – a reference to hard times when families could not afford salted meat to season their beans. One of the first recognized zydeco artists was Amede Ardoin, who made numerous recordings in the late 1920s and 1930s, setting the standard for generations to come. His own family legacy provided plenty of its own zydeco history along the way, and now his descendants Sean Ardoin and Chris Ardoin both front Lake Charles-based bands that often visit New Orleans. Clifton Chenier took the mantle of “king of zydeco” and during the 1950s and ’60s blended in R&B and rock sounds for a more swinging evolution of zydeco. The styles of today’s players now span from traditionalists like Boozoo Chavis to wide-ranging and flamboyant Buckwheat Zydeco.

Finding Zydeco

Because zydeco is so strongly associated with the culture of south Louisiana, visitors to New Orleans are often surprised to find that relatively few clubs offer live zydeco music on a regular basis. Jazz, New Orleans-style brass bands, blues, rock and funk are much more prevalent in the city than either zydeco or Cajun music. That’s because most zydeco musicians come from southwestern Louisiana and east Texas – from the communities in and around Lafayette, Lake Charles and Houston – and when they aren’t touring the country or abroad tend to play closer to home.

But visitors usually stand a good chance of finding some live zydeco on any given night in New Orleans. The richest local harvest of zydeco comes when a New Orleans music festival is taking place – especially the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival (www.nojazzfest.com), the French Quarter Festival (www.fqfi.org) – both held in the spring – and the Swamp Fest (www.auduboninstitute.org), held Uptown in the fall. Year-round, the most reliable venue to find zydeco in New Orleans is Mid-City Lanes Rock ‘n’ Bowl, an inviting venue for local regulars and visitors alike where some of the top names in zydeco hold court on the stage. In the French Quarter, some clubs on Bourbon Street periodically host zydeco acts, especially the Old Opera House (601 Bourbon St., 504-522-3265), where Dwayne Dopsie and the Hellraisers frequently play when they are not touring. Also, Bruce “Sunpie” Barnes – the one-time Kansas City Chiefs pro football player – plays a blend of zydeco, Caribbean and blues music with his band Sunpie and the Louisiana Sunspots. They regularly perform at venues around New Orleans, where Barnes also works as a ranger at the National Park Service’s French Quarter unit (419 Decatur St., 504-589-4841).

For recorded zydeco, check out the extensive selection of CDs at the Louisiana Music Factory (210 Decatur St., 504-586-1094).

Ian McNulty is a freelance food writer and columnist, a frequent commentator on the New Orleans entertainment talk show “Steppin’ Out” and editor of the guidebook “Hungry? Thirsty? New Orleans.”