Oldest Building Features of the French Quarter

Secluded in the muddle of the French Quarter’s raucous street life linger elements that still impart a kind of stately antiquity. They are Spanish and French-era pieces. Some are rightly celebrated for their survival of the epochs; others, dressed in garish costumes at the shop level, maintain a quiet dignity overhead.

There are only about a dozen known Colonial-era buildings in the Quarter. Surely more would have survived except for two late 18th-century fires. But armed with some simple guidelines, you can recognize the early types.

Check the corner of Chartres and St. Louis streets. There, on the river side of Chartres is a house with a well-known restaurant and a balcony. Note that the balcony is higher than usual, almost too high for the building. The arched, barred transoms under it are bringing light to a short middle floor called an entresol. This is where the old Spanish shopkeeper Juan Paillet kept his wares.

The entresol house was an early experiment in vertical living, with the shop on the ground floor, the warehouse in the middle, and an elegant residence on the upper level. Note the type at 440 Chartres, at Bourbon corner Bienville, at Royal corner St. Louis, and in mid-block at 500 Decatur. Most date to the 1790s.

Brennan’s Restaurant at 417 Royal Street is an example of a more elaborate business and residence of the late Colonial period. Dating to the 1790s, it was once a private bank and home. The Banque de la Louisiane, whose initials are on the balcony, made the building public in 1805. In the early 1900s, it first became a restaurant called the “Patio Royal.” It has been the home of Brennan’s since 1946.

The Girod House at 500 Chartres corner St. Louis, is better known as Napoleon House. Tradition abounds, both as to its one-time purpose as a haven for the deposed Emperor, and in modern times about the charms of its resolutely unregenerate bar. Its rear wing was built just after the Great Fire of 1794. The three-story main part, with its towering belvedere, dates to 1814. Above the tavern is an elegant salon and residence, now restored for entertaining.

Another private home in the grand style was that of Bartolome Bosque at 617 Chartres Street, dating to 1795. Its Arabesque monogram on the balcony represents the style of Spanish Colonial ironworking in New Orleans. This type of home is called a “Creole townhouse.” One accesses the rear by a porte-cochere or carriageway, and ascends the stairs in the rear of the building.

Creole townhouses never had inside stair halls. Bosque’s daughter Suzette was the third wife of the state’s first American governor, W.C.C. Claiborne. On his third try the governor finally married a Catholic, making better friends with the Creoles. She proceeded to outlive him.

Like the Bosque House, the Pedesclaux-Lemonnier House, 640 Royal at St. Peter, has a colonial origin. Begun by the grand old Spanish notary Pedro Pedesclaux, it was sold to a doctor from the islands. In 1811, Dr. Yves Lemonnier had the building enlarged, adding his initials to the balcony. His curved-wall salon on the second floor is the finest in the Quarter. After the Civil War, a later owner added the fourth floor, making it a “skyscraper.” The building was identified with George Washington Cable’s romance “Sieur George” in later decades. Today it is sadly hung with t-shirts.

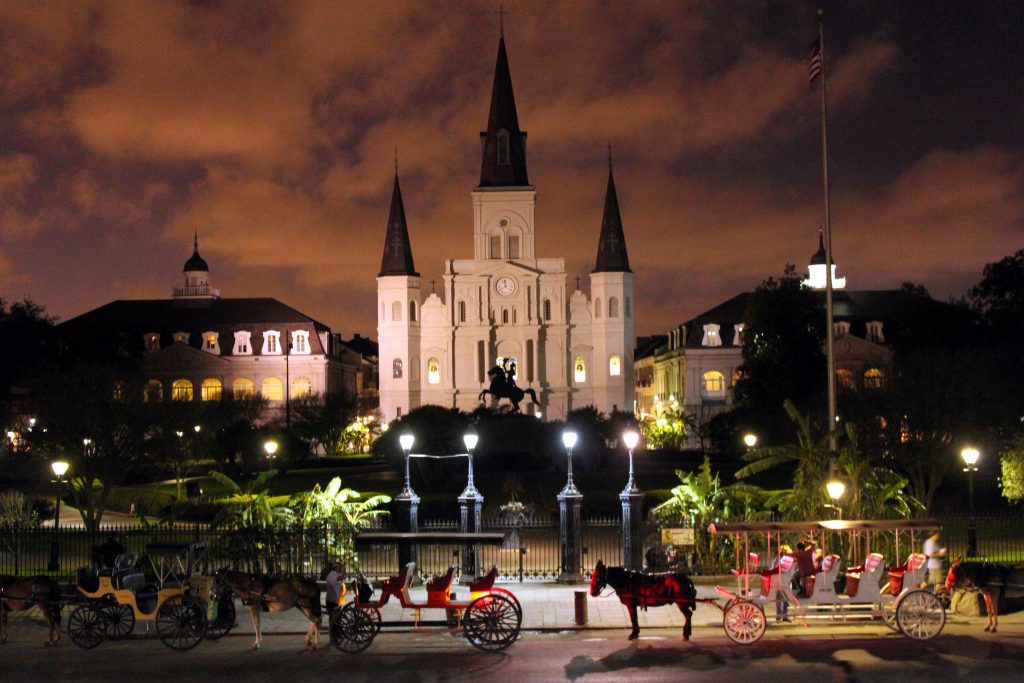

The old Spanish Cabildo and The Presbytere, or priests’ house, flanking the St. Louis Cathedral, were designed for the Spanish governing council by Guillemard, a French-born architect. The Cabildo, built in the style of Spanish town councils in Spain and the Americas, was begun in 1795.

The Presbytere has never housed clergy, although buildings underlying its site were always the priests’ residence. Also begun in 1795, it was not completed until 1847 and was used for most of its history as a courthouse. The Mansard roofs on both buildings were added in 1847. For nearly a century both buildings have been part of the Louisiana State Museum.

“Madame John’s Legacy,” another Museum property at 632 Dumaine, is also named for a romance by Cable. Dating to 1788, it was built immediately after the great fire that year, duplicating the house type of the French Colonial era. With its free-standing mass and surrounding galleries, it is more like a French West Indies home than a Spanish townhouse.

Still, its first owner was a Spanish officer, and its builder was an American, Robert Jones. The hall-less floorplan here is important. It is three rooms wide and two rooms deep with cabinets and cabinet galleries, a derivative of French-Carribbean house types.

The oldest building in Louisiana and the Mississippi Valley is the stately Convent of the Ursulines at 1100 Chartres Street. Designed by a French-trained military engineer in 1745, it was completed in 1753. It resembles the Continental French buildings of the Louis XV period more than colonial institutions.

The façade we see from Chartres is the rear of the building, which faced the river and was surrounded by herbal gardens. The nuns used their herbs and potager to feed their staff, students, orphans, and soldiers whom they cared for in the neighboring military hospital.

Jackson Square, the old Place d’Armes, is the oldest space in the city. Laid out with the town in 1718, it was always the parade grounds. The city began to make improvements to it in the 1830s, adding trees and walkways. The fence and equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson, hero of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, date to the 1850s.

If you’re planning a stay in New Orleans, be sure to check out our resource for French Quarter Hotels.

Sally Reeves is a noted writer, historian, translator, and archivist. She is known for her work in the New Orleans Notarial Archives as “Louisiana’s premier archivist” and her publications on New Orleans history.