Gardens of the French Quarter – St. Anthony’s Garden

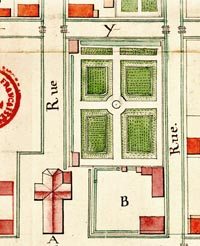

Detail, Ignace Broutin, Plan de la Nouvelle Orléans telle qu’elle estoit le premier janvier mil sept cent trente-deux. French Centre des archives d’outre-mer 04DFC 90A. Broutin’s plan of the garden and the Capuchin complex in 1732. Several drainage features seem to be included. The potager was planted in rows. A decorative feature was at the center. The larger building in the courtyard was the kitchen and refectory. It had a door leading to the garden. One of the other structures was a poultry house. The small brick-between-posts building nearest to the church in the garden was the residence of the Capuchin superior. In later years, Pere Antoine would reside in a small house close to this location.

Bourgerol’s 1838 plan of cathedral properties is the first known official plan showing Place St. Antoine in the center. Joseph Cuvillier, N. P., 10/9/1838, New Orleans Notarial Archives.

St. Anthony’s Garden, August 30, 2005. Photograph by Judy Andry. Courtesy Judy Andry.

Secluded behind the stately towers of St. Louis Cathedral and enclosed by its sturdy old fence, St. Anthony’s Garden is a welcome oasis of calm amid the noisy surroundings of the French Quarter. It is named for St. Anthony but dedicated to the memory of his namesake, longtime Spanish curate Antonio de Sedella, also known as “Pere Antoine.” The melodic notes of the drab grey mockingbird and the clarion whistle of the red crested cardinal offer few interruptions to the garden’s monastic spirit. High above, the tower of the old cathedral shields the garden from the rays of the rising sun, the delicate clangs of its half-hour bells marking time faithfully. Alongside, a pair of strangely-allied alleys hems in the sidelines, one quite agreeably named for the saintly curate, and the other more curiously named for a band of pirates.

Early each morning, artists of the community arrive at the garden’s western exposure, easels and paints in hand. For nearly a century, they have had the privilege of the sturdy bars of the cast iron fence to display their portraits and landscapes in oils and watercolors for passers-by and shoppers. The scene is timeless, reminiscent of Old New Orleans.

Since the founding of the city, there has been a garden here in various forms. The open space is as old as Jackson Square, laid out by the French engineer de Pauger in 1721 as a permanent public plaza for the city. Like the square, the Cathedral garden, used for nearly a century as a potager or formal space for growing vegetables divided by walkways, has evolved over the years. It was initially situated directly behind an earlier version of the Presbytere adjacent to the Church of St. Louis. Formal but practical in purpose, it served the monks both as a place to supply the dinner table and for meditation and the recitation of prayers. After the city’s two disastrous fires of the later Eighteenth Century, the wardens of the cathedral partly filled the garden with rental property to cover the expenses of the parish.

After the death of the revered Pere Antoine in 1829, New Orleans officials moved to convert the old Capuchin space into a public garden for the city. At that time, the bed of Orleans Street entered the square from Royal, extending in to the rear of the old colonial cathedral.

During the 1830s the city closed the Orleans street bed in the square, purchased some land from the wardens, and shifted the garden to the center. The city then built a pavilion and green house, added a fountain, planted flower beds, and leased the space to a vendor. For thirty years in the ante bellum period, Place Antoine was a resort for lovers, the elderly, and families with children. From spring to fall, they repaired to the garden to promenade along its walkways while enjoying an ice cream or a lemonade under a canopy of flowering magnolias.

In 1849, the Wardens of St. Louis Cathedral commenced the building project that replaced the old Spanish cathedral with the present building and fence. Finished in the early 1850s, the cathedral now had a deeper footprint. This made the garden smaller but did not put it out of business. By 1860, it was operating as “Bellanger’s Garden,” open in the spring and summer.

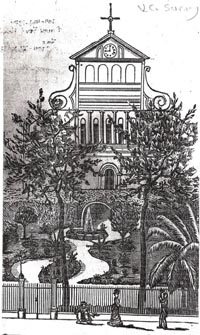

The Civil War put an end to the economic viability of a public garden in the French Quarter. Abandoned, the space grew up into a jungle. Owned partly by the church and partly by the city, its legal status became cloudy. During the 1880s, the first known photographic evidence of St. Anthony’s Garden appeared as a print in a local guidebook. The garden was intact! A fountain splashed in the center. Banana trees and shrubbery flourished. A vine-covered arbor led somewhere, disappearing into the distance. Sinuous walkways led from the gate at Royal to the cathedral. They went perfectly with architect de Pouilly’s signature, scroll-shaped consoles and sightless arches on the rear of the cathedral. Fashionable ladies and gentlemen strolled on the Royal St. sidewalks. Alas, not a soul was inside the fencing. Was the garden public or private?

The first known positive evidence that the church owned the garden dates to the 1890s, when the cathedral budget provided for a gardener. For over a century after that, it has continued in use as a private green space, a visual oasis locked behind its fence. Even so, French Quarter residents and visitors have taken ownership of its presence, feeling entitled to the view. Just looking at the garden brings peace in a hurried atmosphere.

Hurricane Katrina did her best to destroy the tranquil space that had brought so much solace to residents and visitors. But the removal of trees by hurricane forces opened the space to redevelopment. With a newly-opened, sunny exposure, the garden could spring to life in a brand new fashion. Armed with a planning grant from the J. Paul Getty Foundation, the Archdiocesan Catholic Cultural Heritage Center brought in historians, archaeologists, landscape architects and administrators to map out a future for the garden. Funds must still be raised to implement a masterful plan by Parisian landscape architect Louis Benech and associates. Success will bring a certain future as the garden springs to life again in the 21st century.