Is the French Quarter French? Or Spanish?

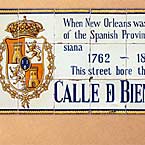

Spanish Influences: Memorial Signage of Original Spanish Street Names, Arched Entresol Building Design, Mezzanine & Courtyard View, and a Covered Courtyard Entryway

The age-old battle between the French and Spanish influence on New Orleans lives on. An intellectually savory argument, like angels dancing, it has fewer participants than in earlier decades when legal scholars contested the French-or-Spanish sources of the Louisiana Civil Code like knights in armor. Today the rivalry between the colonial powers lies mainly in analyzing French Quarter buildings and lifestyles. People ask: is the French Quarter French or Spanish? The arches and courtyards, the funny-looking “in-between floors,” the iron lace galleries, the café life and cooking ways-whose gifts were they? It is a subject for a café au lait at the market or a Sazerac at Napoleon House. After a few of those, the discussion can get heated, particularly when one’s know-it-all brother-in-law claims all the answers.

We confess that the French could have done a better job in the 18th century when the colony was theirs to win or lose. They chose to lose it, but the people chose not to be abandoned. Settlers clung to their French-born language and customs like moss on oak trees. From Paris they ordered all the latest editions of the golden age of Louis XIV and the French Enlightenment, filling their libraries with little 7-inch duodecimo sets of Racine, Moliëre, Voltaire and Rousseau. After forty years of Spanish dominion, they were still cooking with butter, marrying their cousins, avoiding their Easter duties, raising cattle with curious names like Fronzine and Bélizaire, and upholstering furniture with blue and white stripes in the Béarnaise fashion. They still had civil law, Mardi Gras, coffee dripping, the family meeting, sour oranges, sugar cane, Sunday dancing, and heavy gambling. They started drinking chicory coffee soon after French market gardeners began supplying the root of chicorium endiva to Parisian markets. Butchers at the public market-built by the Spanish-were so exclusively French that people began to refer to the French Market, in the “French” part of town, an institution left by the Spanish but built by Creoles and designed by a French native. The Quarter’s par terre gardens continued in the French style with flowers in the middle and walkways on the boundaries. The modern taste for a grassy lawn was either unheard of or an American malady.

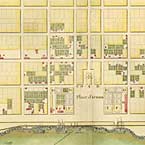

French Influences: City Planning, Creole Cottages, Parterre Gardens, and a City Square ‘Overlooked by Church and State”

But forty years of Spanish dominion left the French Quarter with a semi-fortified streetscape ready for fighting the forces of evil, with phalanxes of common-wall buildings, mysterious alleys, and secluded patios. If the Spaniard’s flat-topped tile-roofed buildings worked better in Sunny Spain than in wet New Orleans, there are still a few out there on kitchens and privies to puzzle the visitor. The Spanish gave us the St. Louis cemeteries, St. Charles Avenue, the first Catholic bishop, olive oil cooking, jars in the courtyard, entresol buildings with mezzanine spaces, Pere Antoine-who was really Friar Antonio, and Baroque-looking government buildings. They also left that queer legal pleading, the non numerata pecunia, sent from the wise Alfonso in the thirteenth century. This rule specified that if the notary did not see money change hands during the course of a mortgage contract, the lender had to renounce his right to sue about it later. The burden of proof fell on him to demonstrate the debt’s existence in alleging non-payment.

Foundations laid by the French and Spanish in the 18th century survived to shape the course of history in the city. The city plan, the central square overlooked by church and state, French arpents, city lots, faubourgs, heavy trusses, Creole cottages, the old Convent, and Charity Hospital came from the French side. But streetscapes full of repeating arches, Arabesque ironwork, covered passageways, and the still-alluring sense of guarded privacy came from His Catholic Majesty of Spain, not His Christian Majesty of France. If it all sounds confusing and unresolved, we invite your opinion. See you at the café?

Sally Reeves is a noted writer and historian who co-authored the award winning series New Orleans Architecture. She also has written Jacques-Felix Lelièvre’s New Louisiana Gardener and Grand Isle of the Gulf – An Early History. She is currently working on a social and architectural history of New Orleans public markets and on a book on the contributions of free persons of color to vernacular architecture in antebellum New Orleans.